The 1980s were a golden era for TV science documentaries, and as a child obsessed with both science and TV, I watched a lot of them. One of my favourites, watched a dozen times or more on a worn VHS cassette1, was an episode of the Channel 4 “Equinox” documentary series called “Chaos”, in which a series of men2 who look like extras from the Big Bang Theory explained how systems built on very simple principles would start off stable could be made to slide into a strange sort of ordered disorder with just a little push. This was interspersed with lots of trippy 1980s graphics of things called “strange attractors” and “fractals” set to an ominous Mahler soundtrack. I was enthralled.3 Here it is, thanks to the magic of the internet:

The dudes 24 minutes in are very much living up to the stereotype of science nerds

Electoral chaos theory

The message of that documentary stuck with me. Ordered systems built around simple principles can be stable and predictable until you make a few tweaks to the rules, or apply just a little extra pressure. The effects can escalate and cascade rapidly as order gives way to chaos. But the resulting chaos isn’t pure randomness, but something much more interesting: order and disorder intertwined. If we map a chaotic system carefully we can often figure out areas of order where we can make confident predictions, and areas of pure randomness where we just have no clue what comes next.

Chaos theory provides an interesting lens for thinking about our current political situation. Post war British politics was a system built around simple principles - two big parties competing for office, with voters swinging between government and opposition. This system was stable and predictable for long time, but faced steadily rising strain. The choices available to voters have steadily increased, and changes in voter behaviour have become harder to parse, culminating in the contest we saw this July, where the electoral map resembled one of the fractal computer graphics in my 1980s documentary. A steady rise in the choices on offer to voters, and in the range of choices they find attractive, has shifted electoral politics from order to chaos.

Bob Devaney and his magic magnet pendulum provides a nice illustration of how extra choices make for chaotic outcomes ten minutes into the Equinox documentary. A traditional pendulum moves back and forth in a very predictable way, but Bob’s magic pendulum does not. There are a series of magnets all attracting the ball in different directions and while all of the forces are orderly and predictable in isolation, which attractions will prevail to move the ball next are all but impossible to predict.

Britain’s traditional two party electoral system was like a traditional pendulum - indeed the swingometer which gives this substack its name is based on the image of an electoral pendulum swinging backwards and forwards. But the pattern of competition we have now - with five, six or more parties winning substantial shares of the vote is more like Bob’s magic pendulum. Each party acts like an electoral magnet exerting a variable attraction on voters. We can map out and understand the different attractive forces, and sometimes it will be clear which one will prevail. But sometimes several attractions will be closely matched or the attractions may change rapidly. Then it can become all but impossible to know what voters will do next. A chaotic system.

This is just an analogy. I don’t have the mathematical ability or grounding in physics to build a fully worked out theoretical model of electoral competition using the concepts of chaos theory.4 But I think it is a fruitful lens for understanding today’s electoral landscape, where some parts are orderly and predicable, while others are volatile and random, and where political parties must try either to impose order on chaos, or to generate and then surf waves of volatility.

I plan to develop some ideas on what this means for understand the current electoral map and the stakes in the next election in future posts. In this first post I want to set out a little electoral history to illustrate how our system moved, over several generations, from order into chaos.

A brief history of electoral fragmentation 1. The pure pendulum (1945-74)

Bob McKenzie works the OG swingometer for the BBC 1964 election night broadcast

The 1945 election is widely remembered as the first Labour landslide victory, and the start of the transformative Attlee government, but two less noticed features of the contest were also significant. This was the last gasp of the fragmented politics of the 1920s and 1930s - a bunch of smaller splinter groups with overlapping names competed alongside the big three parties (Labour, Conservative, Liberal) in multiple seats.5 And 1945 also marked the beginning of the end of the Liberals as a national force in politics for a generation. The Liberals (including splinter groups) stood candidates in just over half of the country in 1945, and lost more than half of their 56 seats. They carried on falling from there, and by 1951 were down to standing barely over 100 candidates, and electing just 6 MPs. This was the Liberal party who could hold meetings in the back of a taxi.

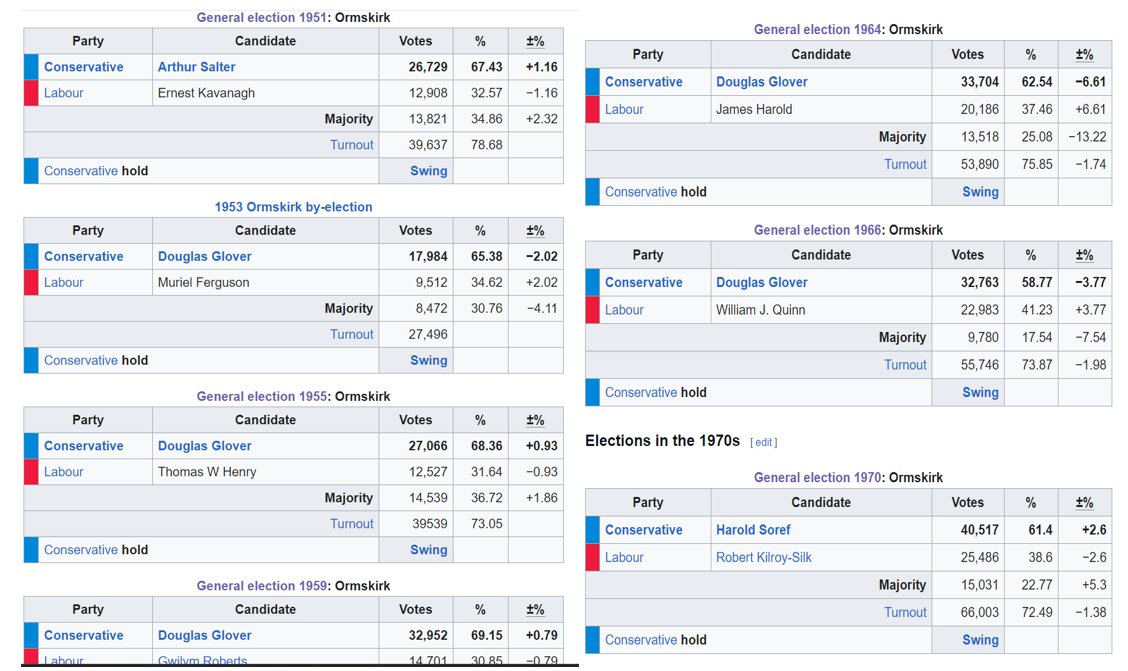

After 1945, a whole generation of voters experienced near-pure two party politics. All the minor parties were all but wiped out, and the Liberals barely clung on in their historic redoubts, unable to muster candidates in hundreds of seats, and struggling to retain their deposit in hundreds more. If you look through the electoral history of many seats, you will find many that look like this:

Elections in Ormskirk constituency 1951-1970

Fun easter egg here for fans of 1980s TV chat shows and 2000s era UKIP

This was the era of the pure pendulum. The two big parties dominated nearly all the contests as either the only options on the ballot pr the only options with any chance of success. These were ordered and predictable elections in other ways too - support for the two parties was bolstered by a deep class cleavage and strong party identities, swings tended to be uniform across the nation, and there were many marginal seats where parties were evenly matched.6 Parties, pundits and pollsters alike could all read across from polls to votes and from votes to seats with a high degree of confidence. While politics is never entirely predictable - stuff happens - this was as orderly as elections were ever likely to get under our system. Don’t like the gang in charge? Vote for the other lot, and if enough of you do so, the other lot get in. That’s all there is.

2. From two to three (sometimes four) 1974-2005

Peter Snow delights psephologists, and confuses viewers, with a giant Triangle of Electoral Destiny, 2005 BBC election night broadcast

The second shift begins in February 1974. The two 1974 elections are generally remembered for the unresolved deadlock between the two parties, seen as symptomatic of the broader stasis and malaise of mid 1970s Britain, a country stuck in the mire, with a political class unable to extract it. But 1974 also saw two lasting changes to party competition. The Liberals, the SNP and Plaid Cymru all stood near complete nationwide slates, meaning for the first time in over two decades most voters could reject both main parties if they wanted. And many did - February 1974 was the first election under the universal franchise where both Labour *and* Conservative support fell sharply. The net ‘swing’ to Labour in this contest reflected Labour falling less (down 5.9%) than the Tories (down 8.5%), and Labour won many seats despite losing support as the incumbent Tory MP fell more. The Liberal vote GB wide more than doubled to nearly 20% , the SNP vote more than doubled to over 20% in Scotland and Plaid Cymru secured their first general election wins in Wales.

The average share of the vote going to the top two parties was 91% in the ten elections held between 1931 and 1970. In the ten elections held between February 1974 and 2010 the average was 75%. This was a decisive shift in patterns of party competition - most voters in most places now had at least three choices, and a substantial chunk of the electorate rejected the “top two” in every election.

But the change shouldn’t be overstated. In most seats, most of the time, Labour and the Conservatives held the top two spots, and the swing between the big two was still the biggest factor deciding the outcome. But the electoral landscape was now too complex for a single pendulum to summarise, and the waxing and waning of third parties was now a central factor in understanding elections. For example, Thatcher’s rise in 1979 was as much about the squeeze of the Liberals (who fell 4.5 points) as swing from Labour (who lost just 2.3%, not all of it to the Tories), while Thatcher’s second win in 1983 cannot be understood without analysing the rise of the SDP, who tried but failed to “break the mould” of two party competition.

3 First signs of chaos (2010-2015)

Swings from Labour to the SNP in 2015 nearly break the BBC election night swingometer

In 2010 we got the first hints of a new, more chaotic electoral process. The short campaign supposed to be a contest between a Labour government wounded by recession and a Tory opposition rejuvenated by David Cameron’s leadership. Instead it was dominated by a massive surge for the third party, as a strong performance for Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg triggered “Cleggmania”, and with the polls showing an even three way split between the parties, the outcome in hundreds of seats looked all but impossible to predict. In the end, the Lib Dems hit an all time high in votes yet managed to lose seats, Labour support crashed yet the Conservatives were unable to win a majority.

There was also a big step up in fragmentation further down the ballot - UKIP become first party since Liberals to stand 500 plus candidates and gained nearly a million votes, the far right BNP put up over 300 candidates and won half a million votes, and the Greens put up 310 candidates and won a quarter of a million votes and elected their first MP in Brighton.

With more voters than ever able to choose between four or more national parties on their local ballot paper, the share of the vote going to the top two parties fell to its lowest level since 1923. And with no party able to command a Commons majority, the two fresh faced young men of opposition, Cameron and Clegg, formed the first Coalition government since the Second World War.

The 2015 election, which ended that Coalition, has a good claim to be the first truly chaotic multi-party election. Even in 2010, the swing in votes and seats between the two biggest parties was still the main event. In 2015, the modest Tory to Labour swing in England and Wales became a minor subplot in an election dominated and largely decided by huge flows of votes to and from smaller parties outside the top two, with massive divergences in voter behaviour across nations and regions.

The Liberal Democrats suffered a total collapse, losing two thirds of their vote and 49 of their 57 seats. Most of these seats went to the Conservatives, driving Cameron’s party to a majority despite a substantial Tory to Labour swing. In Scotland the Labour party suffered a total collapse, as the SNP surged from 20% to nearly 50%, achieved the largest swing in any constituent nation of the UK since 1918, took 56 of Scotland’s 59 seats, and nearly broke the BBC’s swingometer.

Fragmentation accelerated further down the ballot too, with UKIP become the most successful new party since the emergence of Labour, standing 624 candidates and winning 3.9M votes, but with that vote evenly spread they managed to elect just one MP. The Greens also stand a record slate of 538 candidates and won over a million votes, but like UKIP their vote was widely spread and their only MP remained Caroline Lucas. While these two parties could only summon a mixed doubles tennis pair between them in Parliament, the flow of millions of votes from the three older national parties to these two new forces played an important role in many seats.

4. The Brexit interlude (2016-2019) - “ersatz two party politics”

Dominic Raab holds on in Esher and Walton, helped by the absence of a Brexit party candidate

From the vantage point of 2024 it looks peculiar to call 2015 a point of maximum chaos. The forces unleashed by the EU referendum the next year shook the entire system. Yet while the waves of change and disorder sweeping through Parliament and the parties were unprecedented, in electoral terms the Brexit years marked a brief return to an earlier model, as the centrifugal force of the binary Brexit choice drove a reversed the previous fragmentation and forged a return to “ersatz two party politics.7”

As voters rallied behind the flags of “Leave” and “Remain”, the share of the vote won by the top two parties returned to levels not seen since 1970. The Libera Democrats stuggled to shake off the taint of Coalition, while both the Greens and the parties of the radical right slumped as the mainstream parties polarised and occupied their terrain. Theresa May’s embrace of Brexit did for UKIP, while Green voters loved Jeremy Corbyn’s “new kind of politics.” Both parties lost two thirds of their vote in 2017, a collapse exacerbated by a sharp decline in candidates standing. In 2019, the restriction of voter choice was more deliberate - Nigel Farage stood his Brexit party down in over 300 Conservative held seats. While the move was presented as an effort to help Boris Johnson “Get Brexit Done”, it in fact achieved the opposite, as the enduring appeal of Farage’s brand diverted proved sufficient to deny the Tories victory in dozens of Labour held target seats.8

But, as Philip Cowley and Dennis Kavanagh observed in 2017, this was “ersatz two party politics” - the forces that had built and bolstered the two party model of the post war decades were gone and did not return. Instead a shock to the system forced people into temporary alliance with the big two parties while the question of Brexit remained live. The unwieldy Johnson coalition was always going to be hard to hold together once it achieved its headline goal to “get Brexit done”, and the 2019 performances of both the Brexit Party in Labour seats and the Liberal Democrats in Tory Remain seats underlined the continued appeal of alternative options even during peak Brexit.

5. Brexit done, chaos unleashed (2019-2024)

Liz Truss setting records for being bad at politics, again.9

The disintegration of party competition recommenced the day Boris Johnson achieved his oft-repeated goal to “Get Brexit Done”. The issue which had monopolised the attention of most voters and the entire British political class disappeared within months, never to return. The allegiances and antipathies Brexit forged in the electorate still lingered, but they no longer constrained. Voters began to shop around again very quickly.

While Labour dominated the national polling from 2022 onwards, returning to strength in local government and achieving a string of record by-election, there were also plenty of signs that a new and more fragmented political landscape was emerging. The Liberal Democrats won several record by-election victories, demonstrating they now had a powerful appeal in Southern England. Both the Liberal Democrats and the Greens made huge breakthroughs in three successive local election cycles from 2022, building powerful local platforms for the general election to come, while in May 2024 Labour suffered extraordinary slumps in support in areas with large Muslim populations, suggesting unrest over the Gaza conflict could have major electoral consequences. Meanwhile ReformUK, perennial under-performers in local politics, were steadily rising in national opinion polling.

While the biggest headline from the 2024 contest was of course Labour’s landslide, the statistics on volatility and fragmentation were remarkable: the largest ever drop in one party’s support10; the lowest Conservative vote share ever; the most seats lost by a government ever; the largest number of seats changing hands ever;11 the most incumbents ever to fall directly from first to third or fourth place; the best radical right performance ever on votes and seats; the best Green performance ever on votes and seats; the best independents performance since 1945 on votes and seats; the most Lib Dems seats since the 1920s; the most seats won with less than 35% of the vote. The record for the largest Conservative to Labour swing was broken in 47 seats, and Labour won its biggest ever “winner’s bonus” from the electoral system, in one of the most disproportional first past the post election results ever seen anywhere in the world.

Our old maps don’t work here

Generations of two party domination mean the habits of interpreting elections in two party terms are deeply engrained. But our mental map of an election as a swing of the pendulum between two big parties just doesn’t work as a way of understanding the 2024 result. Yes, the Tory to Labour swing still mattered, a lot, but not only was this swing itself more variable than ever, it is now only one aspect of a much messier picture, and often not the most important one. A uniform Tory to Labour swing, with no changes in the other parties’ performance, would likely have a hung Parliament or a small Labour majority at best. Instead Labour won a landslide with practically the same vote share as 2019. Electoral chaos - fragmentation across more parties than ever, all with their fortunes varying wildly across different kinds of seats - is the key to understanding how that happened.

In a chaotic election parties and partisans can be tempted to pick the subplots best flatter their prejudices. Was this the biggest landslide in a generation? Yes. Was it also the most fragile landslide in ever, driven as much by divided and weak opponents as a strong victor? Also yes. Was Tory defeat driven by a split right? Yes. Was Tory defeat driven by losing their moderate heartlands? Also yes. Complex and variable outcomes can be cherry picked to support any argument. Choose your own adventure. All of them contain grants of truth, but none of them is the whole picture. Chaotic elections resist simple one line summary and “just one trick” responses are unlikely to work.

The chaotic 2024 outcome also greatly complicates assessment of the polls as an indicator of parties’ relative standings. Aggregate poll numbers are all but useless as a guide when so much turns on geography and local variations in opponents’ strength. Labour, for example, could win another big majority with a lower overall vote share than now, or lose their majority altogether with a higher overall vote share - everything depends on where the gains and losses fall, and how local competitors fare. In such an environment, local elections and by-elections gain value, as indicators of shifting local tides, and MRP modelling becomes more useful as it can, to some extent, map local variations in competition and voter preferences.

But even more sophisticated tools still leave us flying in a thick fog, as the complex flows of the vote between five or six parties are very hard to map effectively, and may change again in the short campaign. Today’s fragmented politics is Terra Incognita. Impossible things are now possible, and implausible things will happen more often than we expect. Our old maps won’t work here. Time to build some new ones.

Look it up kids!

And it is all men, including the narrator. 1980s science documentaries were *very* male.

I bought a heap of books on the topic as well, most of which went way over my head, but I recommend “Chaos” by James Gleick which was a fantastic guided tour for the general reader.

Fun PhD opportunity here for someone smarter than me with a physics or maths background?

Parties putting up multiple candidates in this contest included National Liberals, the Independent Liberals, National Independents, Independent Nationalists, Independent Progressives, National Labour, Independent Labour Party, Common Wealth, and the Communists. Most of these had vanished by 1951.

Nerdier readers keen to learn more should check out Butler and Stokes’ “Political Change in Britain”, one of the all time classic books on electoral books, analysing the very first British Election Studies which were fielded in 1964-70, which by coincidence turned out to be the final elections in this orderly phase.

Cowley and Kavanagh (2017) “The British General Election of 2017”, p.417: “The parties now have new and perhaps uneasy coalitions of support…[I]t is far too early to know how stable these coalitions will prove; they could well collapse just as speedily as they seemed to arrive.”

See analysis by Curtice, Fisher and English in chapter 13 of “The British General Election of 2019”. Several current Cabinet members including Ed Miliband and Yvette Cooper may have Farage to thank for their continued presence in the 2019-24 Parliament.

Records Liz Truss now holds: shortest ever tenure as Prime Minister, lowest ever approval rating for a Prime Minister, largest ever one month decline in approval ratings as Prime Minister, largest ever Conservative to Labour swing (25.8 points), largest ever Conservative majority lost in defeat (26,195), first former Prime Minister to lose their seat since Ramsay MacDonald. The Labour candidate who defeated Truss set a new record for the lowest winning vote share for a victorious Labour or Conservative MP (26.7%).

Four of the six largest declines in national vote share have all come in elections since 2015 - Conservatives 2024 (19.9%), Liberal Democrats 2015 (15.1%), UKIP 2017 (10.8%), Labour 2019 (7.9%)

303 - 47% of all seats

Well, if it’s chaotic, there no longer are any maps. You should therefore I think take that analogy seriously and find a mathematician to tease it out.

At a technical level, it seems at first sight correct to me. In the 50s, share of vote for, say, Labour mapped smoothly into seats won. Now it doesn’t.

But then, if the MRP models work, then there’s enough predictability to say it’s not chaotic. You just have to consider more variables in your model. So maybe not literally chaotic, just highly unstable.

But I’m not even sure that’s right. I have this sense that voters have imbibed the tactical voting idea so deeply that even the idea of party allegiance is dissolving. That is, it’s not just people having an allegiance that switches but rather they have some kind of end result in mind and will alter who they vote for to achieve that. Maybe a larger range of ends - eg “Keep the Conservatives out” - in the polling would reveal more underlying stability.

Finally, since the key question is Who Wins, it’s possible that another dynamic theory from your childhood might be more important, Catastrophe Theory, of which Warwick was the centre. This is a framework for understanding why systems flip rather than evolve into new states.

Given where we are now, and FPTP as our voting system, is it any wonder that faith in politics and politicians is falling? A more proportional system could lead to consensus driven policy making, but both of the big parties believe in ‘one more go at getting a majority’ and are prepared to wait many years in opposition to achieve it.

I find it all very depressing.