Labour: How bad is it?

The polling picture 14 months in is not pretty

Labour activists and MPs have emerged from their party conference feeling remarkably chipper, buoyed by a leader’s speech which reminded them that being in power is good, and manged to draw dividing lines with the party’s Conservative and Reform opponents and even gave the party’s often disappointed liberals and progressives some lines to cheer. The power of adversity to rally partisans together should not be underestimated, but conferences seldom change the broader political weather, and grim polling continues to thud into Labour inboxes like a killer post Mirror party hangover.

The leadership will say it is still early, and they are right to do so - as the Swingometer discussed early in Rishi Sunak’s time in office, three quarters of post-war governments have bounced back from a mid-term polling slump. Yet, as Sunak’s fate last July also shows us, a severe and sustained downturn can be electorally lethal. Labour have clearly lost ground since taking office, but is this a typical bout of the midterm blues, or something more serious?

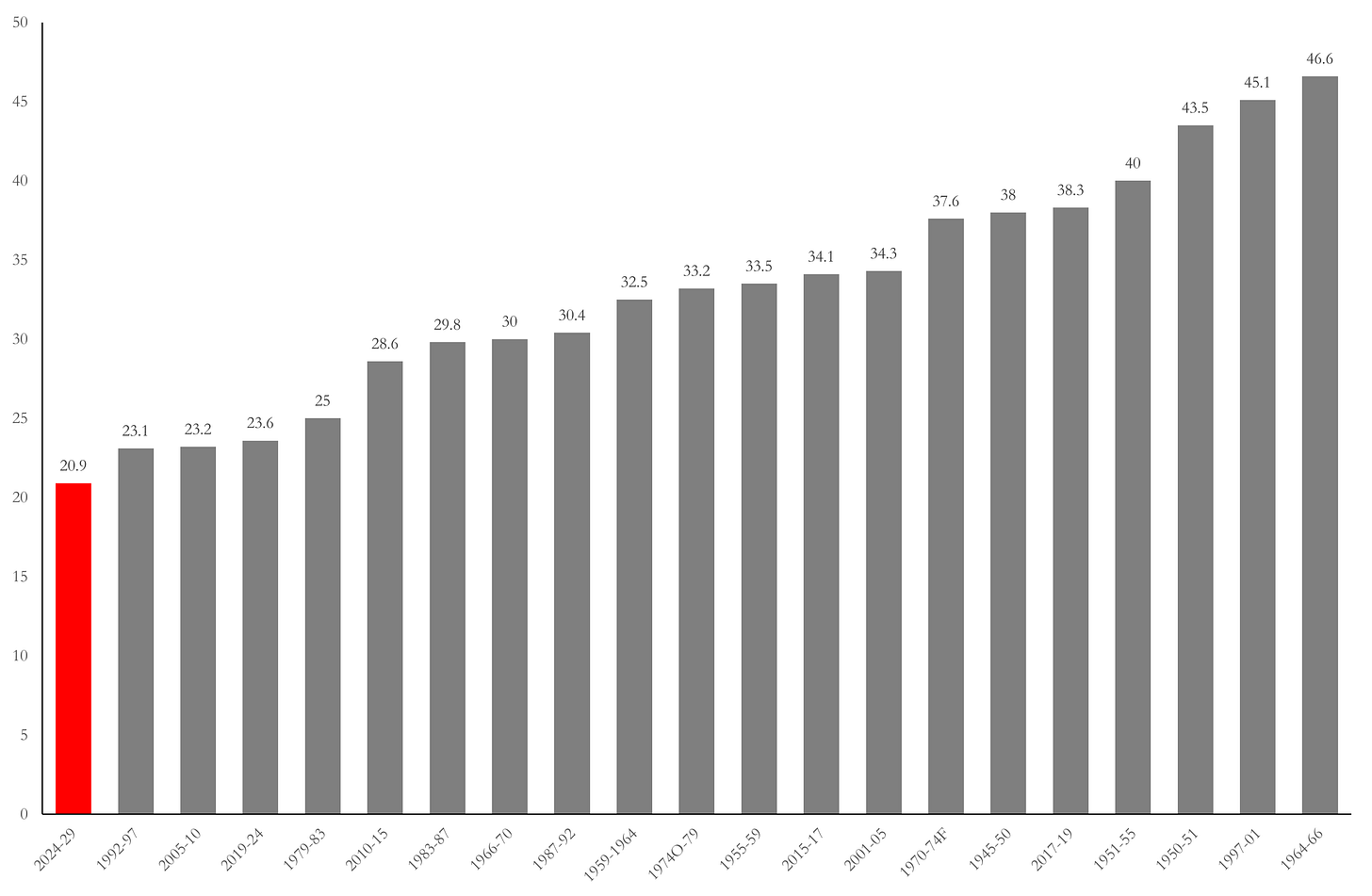

The new Labour government have already set one unwanted polling record. As Figure 1 illustrates, Labour’s average share in the latest polls is just 20.9%, meaning the Starmer government has already fallen lower with the electorate 14 months in than any previous government at mid-term, surpassing even the dire slumps suffered by the Conservatives under John Major (23.1%), Liz Truss (23.6%) and Margaret Thatcher (25.0%) and the previous Labour low under Gordon Brown (23.2%). And all four of the previous governments to fall to 25% or below hit their low ebbs in the middle of severe financial storms - Starmer has slumped still lower at a time of (relative) market calm.

Figure 1: Lowest governing party monthly poll averages at mid-term 1945-2025, lowest to highest

Source: Mark Pack PollBase Q2 2025 update, current Labour poll average calculated from latest polls published by YouGov, MoreInCommon, Survation, Opinium, FindOutNow, Techne, Ipsos and Lord Ashcroft Polls

The picture is almost as grim when we look at the size of swings against governments in the first14 months after an election. Support for Starmer’s Labour has dropped by nearly 14 points in the first 14 months after the election, the second largest drop in post-war political history, and four times the average post-election polling drop of 3.5 points. Only John Major, presiding over economic chaos in the wake of the Exchange Rate Mechanism crisis, fell further and faster in his opening year and a bit. And while most governments suffer an early slide, Starmer’s polling slump contrasts starkly with the warm welcome received by the last two Labour Prime Ministers taking office after a long period of Tory rule - support for Labour rose by over seven points during the opening phase of Harold Wilson’s 1964 government, while for Tony Blair, polls could only get better , as he rose by a record 8.6 points in his first 14 months after the 1997 election.

Figure 2: Drop in governing party support over 14 months 1945-2025, largest to smallest

Source: Mark Pack PollBase Q2 2025 update, drops relative to Great Britain vote share in previous general election as polls do not include Northern Ireland. Current Labour drop based on poll average explained in Figure 1.

Labour also began weak in 2024, taking office with the lowest vote share of any incoming governing since World War II - so it is no wonder that a large polling slump has reduced them already to the worst polling for any post-war government. But there is one silver lining in the polls - record unpopularity for the incumbent party has not translated into massive poll leads for the largest opposition party. As figure 3 shows, Labour currently trail Reform by 10.3 points in the polls, a worrying deficit to be sure but not a large one by historical standards. Several earlier governments have overhauled larger midterm deficits than this and won again.

Figure 3: Largest opposition poll leads at mid-term 1945-2025, largest to smallest

Source: Mark Pack PollBase Q2 2025 update, current average opposition poll lead based on averages explained in Figure 1.

How can Labour be posting the lowest ever vote shares, after the second largest ever drop in support from the weakest ever starting position, yet not be miles behind? The answer is fragmentation. While Labour have lost support, no single opponent has gained - indeed the Conservatives, still the official opposition having finished second in votes and seats last July, have also gone backwards, losing around seven points in the polls. Instead voters have scattered to the winds, entrenching and intensifying the fracturing of support across five or more parties already evident last summer.

As recent analysis by Jane Green and Marta Miori, and by Dylan Difford, has shown Labour are currently losing votes in all directions - to Reform, the Lib Dems, the Greens and to “don’t know”. While competing on multiple fronts complicates the task of recovery, a fragmented landscape also prevents any single competitor from building a dominant lead. Even a modest recovery to the mid-high 20s could be enough for Labour to be electorally competitive once again in a contest featuring five parties polling over 10%.

Not many cheers for Keir

A well liked leader seen as delivering on voter priorities could therefore have a good shot at turning things around. Unfortunately for Labour, the news from polling on that front is not great either.

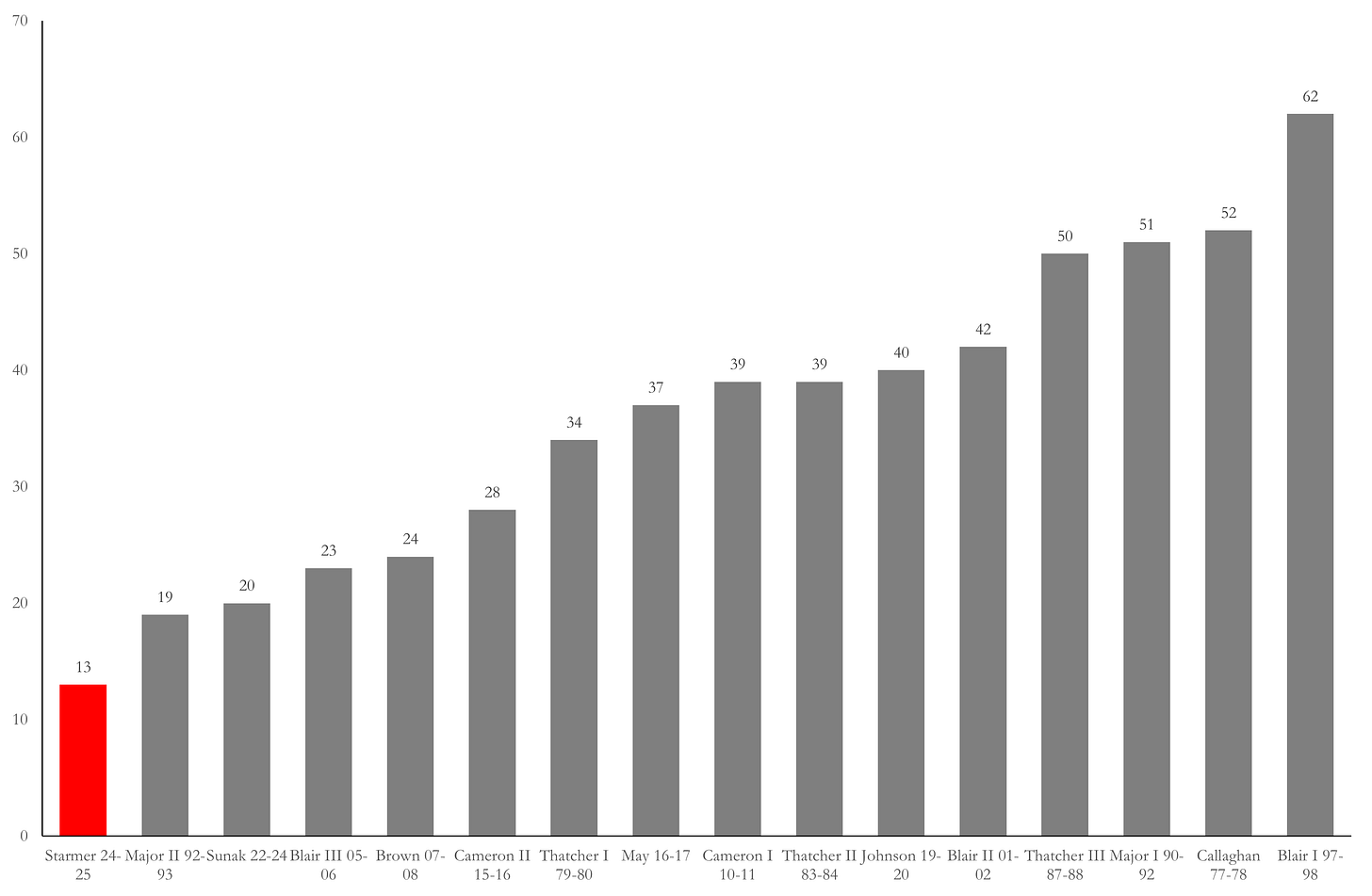

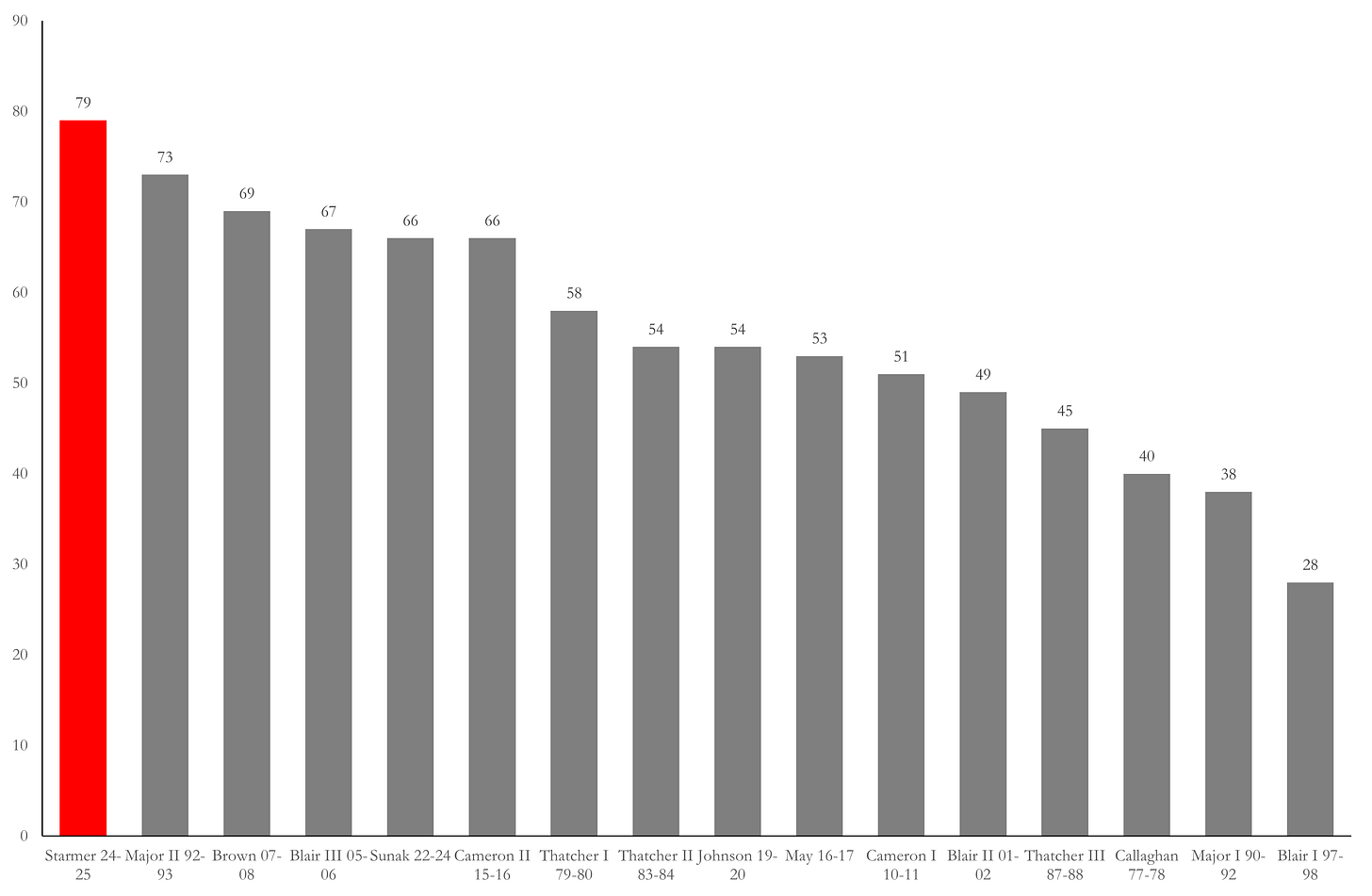

The pollster Ipsos have published leader satisfaction ratings is most months since 1977, one of the longest running consistent polling questions in Britain. Figure 4 compares Keir Starmer’s positive approvals to those of his predecessors 14 months in to each Parliament, while Figure 5 shows the shares disapproving of each PM at this point. We define the starting points here in two ways - from the date of a new election, or from the date of a new Prime Minister. So, for example, John Major can be tracked both from when he replaced Margaret Thatcher in 1990 (Major I) or from when he won the 1992 general election (Major II).

After 14 months in the job, Keir Starmer now has the worst satisfaction rating Ipsos have ever recorded for a Prime Minister. Just 13% of voters gave Starmer a positive rating in the most recent Ipsos poll, worst than John Major post ERM (19%), Gordon Brown at the depths of the financial crisis (24%), Rishi Sunak on the eve of a landslide defeat (20%) or Tony Blair just before his departure from office (23%). Meanwhile, nearly eight voters in ten respondents (79%) tell Ipsos they are dissatisfied with Starmer’s performance, substantially worse than all of his predecessors.

Figure 4: Satisfaction with Prime Minister after 14 months, PMs since 1977, lowest to highest

Source: IPSOS political monitor

Figure 5: Dissatisfaction with the Prime Minister after 14 months, PMs since 1977, highest to lowest

Source: IPSOS political monitor

As well as the lowest approvals in history, Keir Starmer has suffered one of the largest approval drops in his first 14 months. Figures 6 and 7 show the changes in satisfaction and dissatisfaction, ordered from worst to best. Nearly a quarter of the public stopped approving of Keir Starmer in his first 14 months, a drop beaten only by John Major after the 1992 election, who lost the approval of 36% while presiding over a currency crash, an interest rate spike and a recession. Nearly half of the electorate (49%) have switched to disapproving in Keir Starmer in the same period, a negative swing matched only by Gordon Brown, whose early months coincided with the Global Financial Crisis.

Figure 6: Change in satisfaction with the PM in first 14 months, PMs since 1977, largest to smallest

Source: IPSOS political monitor

Figure 7: Change in dissatisfaction with the PM in first 14 months, PMs since 1977, smallest to largest

Source: IPSOS political monitor

Polling on the issues: stumbling first steps

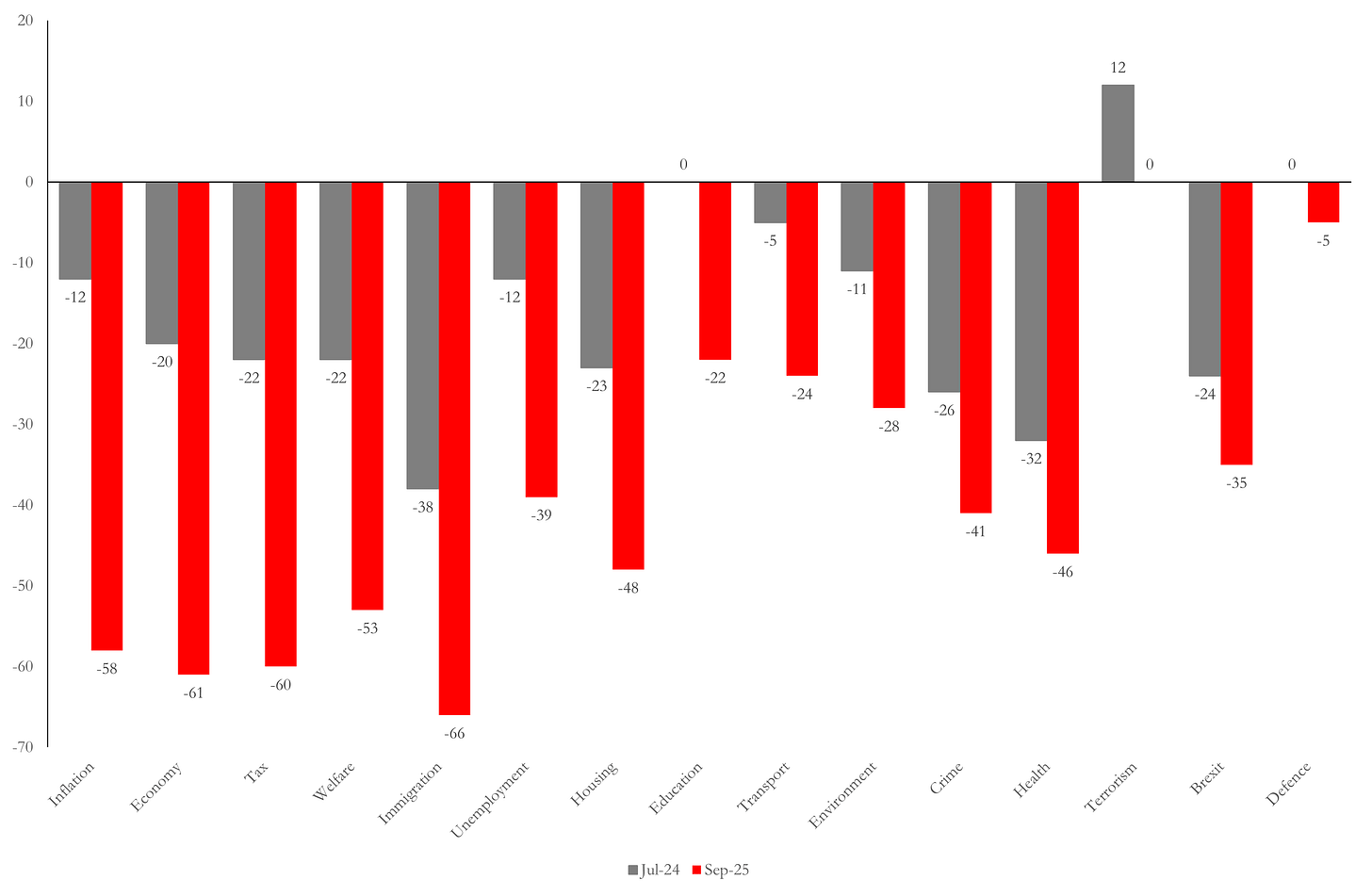

It might help if Starmer’s unpopularity was offset by positive ratings of his government’s performance on key issues. But there is no joy for Labour on this front either.

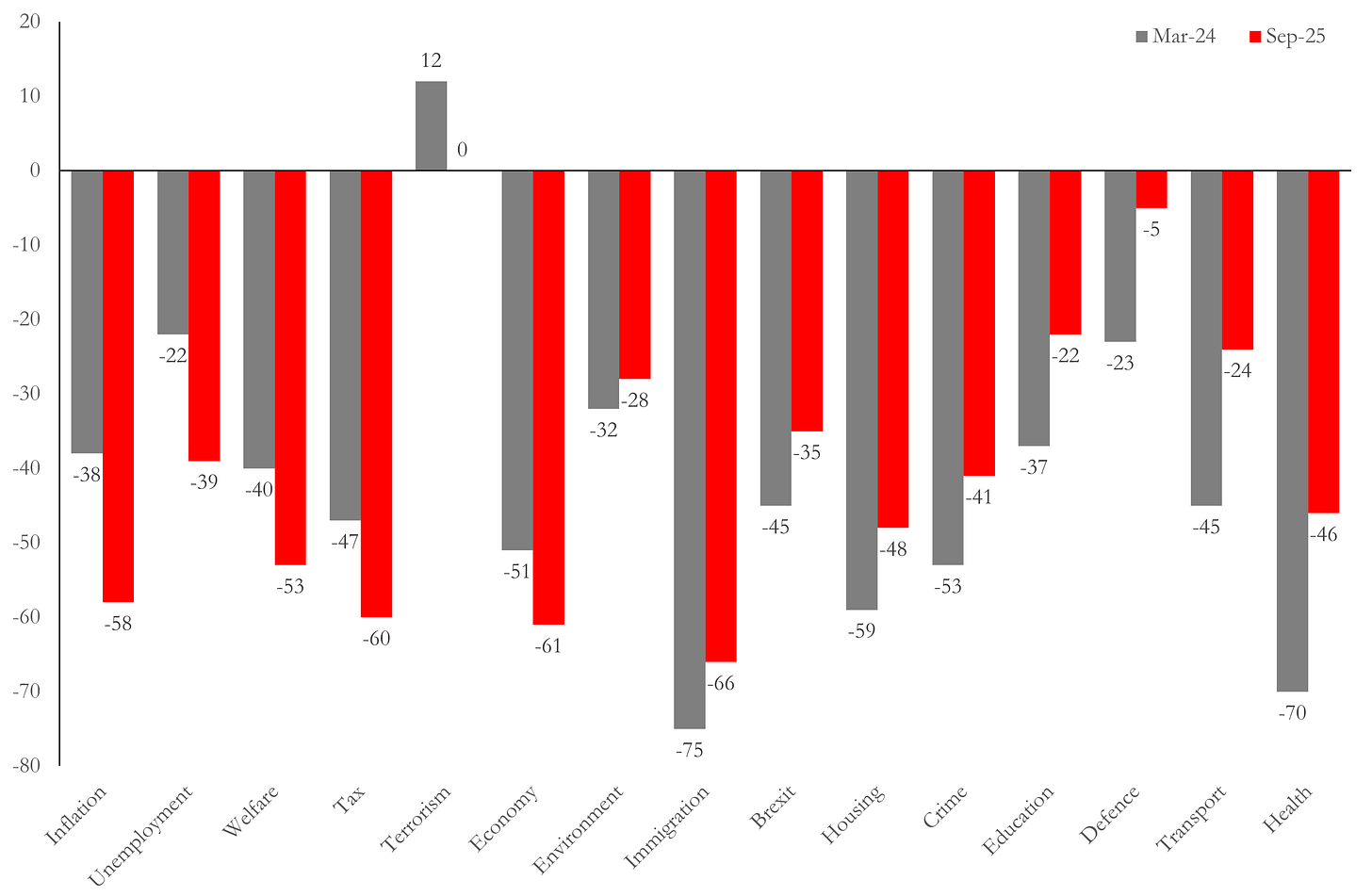

Figure 8 shows net Labour approval ratings on a range of key issues in July 2024 (grey) and September 2025 (red), ordered by the scale of decline recorded by YouGov who track all of these issues regularly. Approvals of the Starmer government have fallen on every issue monitored by YouGov and, ominously for Labour, the biggest declines have come on economic competence issues. Ratings of the government’s performance on inflation have fallen from -12 to -58, on tax the decline is from -22 to -60 and on economic management in general the fall is from -20 to -61. There is also a big fall in the government’s approval on immigration, now rated as the top issue facing the country, where Labour receive there most negative net score on any issue: -66. The landscape is less bleak on Labour’s traditional strong point of public services, but only relatively so - net ratings on health (-46), transport (-24) and education (-22) are all down sharply and in the red.

Figure 8 - Net approval of Labour performance on issues July 2024 (grey) and September 2025 (red) ordered from largest to smallest decline

Source: YouGov

A comparison with the Sunak government’s ratings with the same pollster on the same issues in March 2024, just before last year’s general election was called provides an illustration of just how bad these issue ratings are for Labour. Starmer’s government has already fallen below those of the outgoing Sunak government on every single indicator of economic performance - inflation, unemployment, welfare, tax and the economy in general. Starmer does outpoll Sunak on all the public services issues, in particular health, transport, education and defence. However, despite the attention lavished by Labour on ‘Great British Energy’ the government’s rating on the environment is, at -28, barely better than its Conservative predecessor. Meanwhile Labour’s dire -66 rating on immigration is only narrowly behind the -75 secured by Sunak after his widely derided failure to “Stop the Boats”.

Figure 9: Ratings of the Sunak Conservative government in March 2024 (grey) and the Starmer Labour government in September 2025 (red)

Source: YouGov

The polls, then, are dire: the most unpopular Prime Minister ever heads the most unpopular government ever, with voters already rating Labour worse than the Conservative government they evicted on the every aspect of economic management, and rapidly losing faith in Labour on everything else. The government’s hopes for turning things around rest on two things: doubts and time.

The case for doubting Reform as an alternative government is in principle strong: a radical right party which has only existed for five years and has a polarising leader, a track record of putting up incompetent, toxic and scandal prone candidates, and has no experience of government. Voters may be happy to flirt with Reform as a way to express disappointment in the government, yet wary of casting a ballot which may put Nigel Farage into downing street. This is evidently a popular theory within the govrenment - Starmer and his colleagues now regularly treat Reform as their main opponents, and play up the risks of a Farage government at every opportunity.

But while doubts about Reform are evident in polling, they are not currently blunting the party’s progress at the ballot box. Reform won 40% of the council seats on offer in this May’s local elections, shattering the record for an insurgent party, and, as we saw in last week’s post, Nigel Farage’s party was just as successful at taking seats from Labour as defeating Tory incumbents. Reform also won a Westminster by-election the same day, the first seat any Farage party has even taken from Labour in such a contest, and have continued to take seats from the government in local by-elections all over the country in local elections since May. Whatever doubts voters may have about Reform are not at present sufficient to prevent them regularly beating the government at the ballot box.

Time is the government’s other main ally. Time for outcomes on the economy and public services to improve. Time for the political agenda to change, ideally shifting away from Reform’s favoured topic of immigration as overall migration flows decline, and small boat crossings are reduced enough for the narrative to move elsewhere. Time for Farage to stumble, or for voters to grow unhappy with the councils Reform now runs. Time, perhaps, for the Conservatives to pick a new leader and split the right vote more evenly, to Labour’s benefit. With well over three years left in this Parliament, any and all of these things could happen. It is, after all, only four years since Boris Johnson’s Conservatives were masters of all they surveyed and Keir Starmer looked set to become yet another failed Labour opposition leader. Volatile polling cuts both ways; fickle voters who swing sharply against a government could return just as quickly.

Yet while a fragmented political landscape makes it easier than it might be for Labour to recover from the worst start in polling history, simply hoping for something to turn up may not be enough. Labour’s closing message last summer was ‘if you want change, you have to vote for it’. The government’s polling slump since is a warning from voters that voters will not tolerate a failure to deliver on that pledge. This is the other side to fragmentation: if the government cannot or will not deliver on the mandate for change, there is now no shortage of competitors offering a compelling alternative. This government may still be young, but the voters who backed it to deliver change last year have already given loud notice of their willingness to remove it for the same reason.

A party winning absolute power on just over a third of the vote, was always going to find the going rough. The next election could see an even more unfair result. Faith in politics and political solutions to our society's problems will dwindle further.

The other side of time--which is the reason Sunak called the election for July and not later--is that other parties of your ideological ilk (Lib Dems, Greens, and perhaps the Corbyn party and SNP/Plaid) can take the initiative. One wonders how bad it could get if the Lib Dems started polling ahead of Labour, which is hardly a crazy scenario at this point.