Electoral chaos theory 2: increased local choice and why it matters

More diverse choices on offer means more diverse choices made

A few weeks ago, I set out how British politics has evolved over the past six decades or so from this….

To this….

I’ve labelled our new political landscape “electoral chaos theory” - like the complex systems of chaos theory this is not a landscape pure randomness, but one built on more complex and unpredictable patterns of competition driven by fragmentation across more parties, all with fortunes which vary across different kinds of seats.

In this second post, I’m going to set out one of the ways in which this fragmented new politics has come about, which I call the “choice effect.” This is the way in which just having more options on the local menu changes voters’ behaviour, something which, thanks in particular to the growing strength of two newer national parties (ReformUK and the Greens), was strongly evident in 2024, when more voters had more choices than ever before.

I’ll consider the host of different ways in which these new choices shaped the 2024 contest in the next post in this series, which will look both at “split effects” - where smaller, newer parties have shaved off a distinctive slice of a big, old party’s coalition; and “squeeze effects”, where supporters of two or more parties decide they are willing to team up to defeat a common for.

Then, in the fourth post in the series, I’ll take a look at how these new competition patterns, and the new electoral map they have produced, may shape parties’ strategies and voters’ choices over the course of this Parliament and in the next general election.

The choice effect: why the biggest parties lose ground when ballots get bigger

More candidates stood for election to Parliament in the 2024 general election than in any previous contest: 4,397, comfortably above the previous record in 2010. Every voter in the UK had at least five local candidates to choose from, and more than half could choose between seven or more - much higher levels of local choice than occurred in 2010, as Figure 1 below illustrates. Every new candidate on the ballot gets some support, and those votes have to come from somewhere.1 Labour and the Conservatives are the biggest parties, standing everywhere and taking the top two spots in most places, so they stand to lose the most. They are the strongest parties in most seats, and indeed were the only choices available in many seats until fairly recently.

Figure 1: More local choices - the number of candidates standing in each constituency in 2024 and in 2010 (the previous record year)

Source: Democracy Club; author analysis of BBC 2010 general elections dataset

Part of the rise in candidate numbers is driven by eccentrics who spend a bit of money to get themselves added on the ballot, for example as supporters of the Church of the Militant Elvis party or, worse, Leeds United.2 Such candidates aren’t likely to win and their appeal is obviously pretty niche. But the electorate is large, and contains multitudes. Voters in Rishi Sunak’s seat of Richmond and Northallerton had thirteen options available to them, including independent space warrior Count Binface, post-punk rock star Rio Goldhammer (Yorkshire Party), Monster Raving Looney Sir Archibald Stanton and YouTube prankster Niko Omilana.3 Independents and novelty candidates won over a thousand votes between them - not a huge sum, to be sure, but not peanuts either: the 2% of all votes cast for novelty options is Richmond would be sufficient to change the outcome in more than 40 seats. Even obscure and novelty choices attract some support, and the more of them there are, the more votes they will win, and the bigger the disruption on other parties’ support.

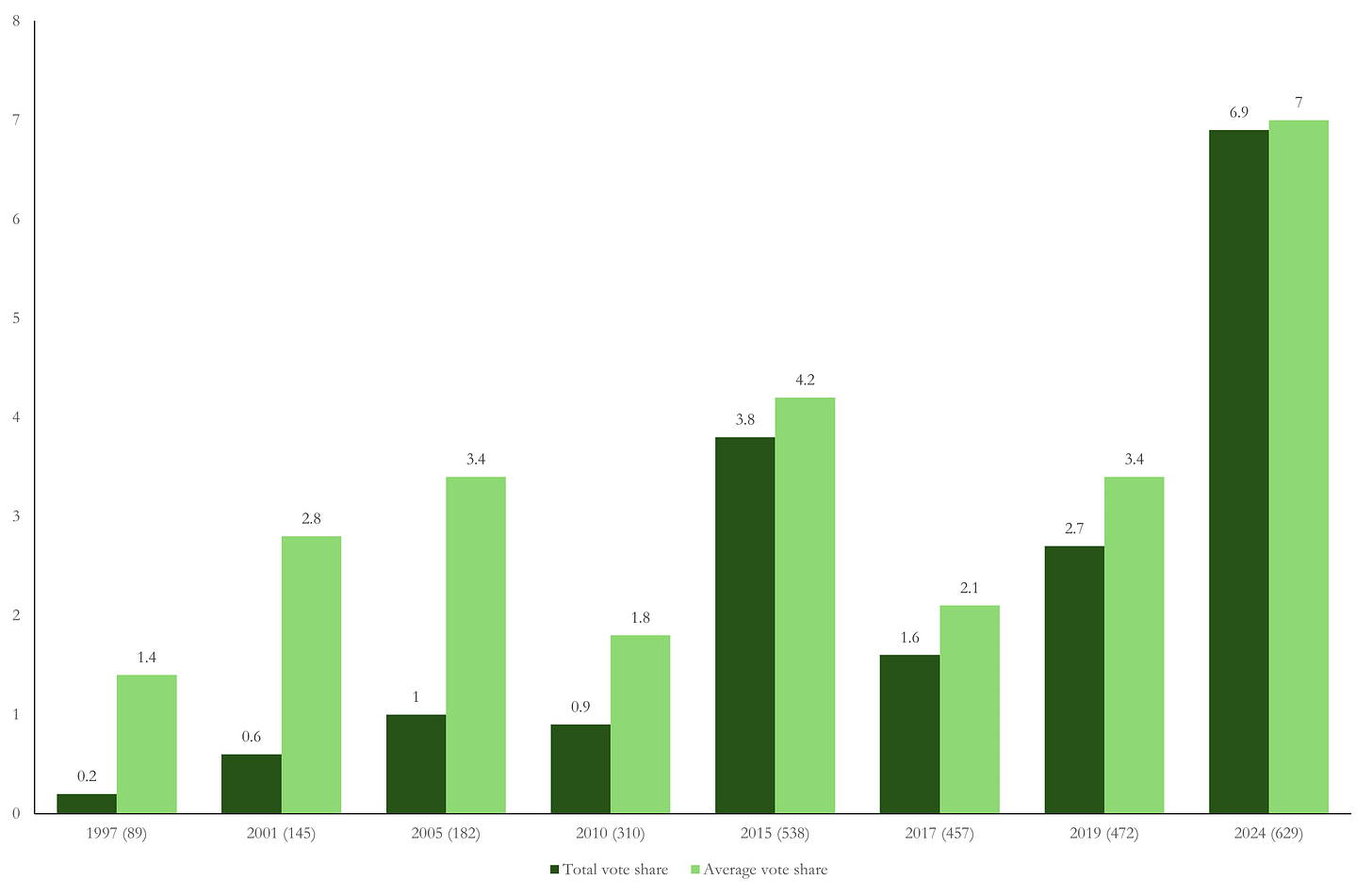

While novelty candidates add colour, most voters take general elections seriously enough to ignore them. The really significant driver of fragmentation is the growing reach of new parties with distinctive national profiles. Two parties in particular provided voters in hundreds of seats with compelling new options in 2024: ReformUK and the Greens. These two parties have clear national brands and distinctive appeal. Both fielded hundreds of extra candidates in 2024 and won record levels of support, as figure 2 illustrates.

Figure 2: (a)Radical right candidates, total vote share & average vote share 1997-2024

(b) Green party candidates, total vote share and average vote share 1997-2024

The previous peak for both the Greens and the radical right (then UKIP) came in 2015, when both parties stood nearly full slates across England and Wales for the first time, though at least one of them (usually UKIP) was absent from most Scottish seats. After 2015, both parties fell sharply in response to shifts in the appeal of the governing parties - the post-Brexit Conservative party absorbed much of UKIP’s support while the Corbyn Labour party won over most 2015 Green voters. Both parties cut their candidate slates drastically, reducing the choices available in most seats - less than half of seats in any British nation featured a full slate of large party candidates in 2019, with Nigel Farage’s decision to stand down candidates for his UKIP successor - the Brexit Party - particularly significant, curtailing five party competition in over 300 Conservative held seats.

In 2024, for the first time ever, both the Greens and the radical right were present on the ballot nearly everywhere in mainland Britain, with Reform standing 609 candidates and the Greens standing 629. As figure 3, shows this meant 95% of constituencies in England featured candidates for all of the “big five” national reach parties, 97% of seats in Wales featured all of the “big six” (the big five plus Plaid Cymru) and 77% of seats in Scotland featured all of the Scottish “big six” (the big five plus the SNP). These figures are above the previous 2015 peak in all three countries, and dramatically higher than the numbers for the 2017 and 2019 elections.

Figure 3: Share of seats where all of the ‘big five’ or ‘big six’ stood candidates 2010-2024

Source: Author analysis of BBC elections datasets. ‘Big five’ = Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, UKIP/BrexitParty/ReformUK ‘Big six’ = Big five plus SNP (Scotland), Plaid Cymru (Wales)

While each party’s support had its own geography and distinctive dynamics, as we shall see, the sheer fact of more choice on the ballot paper played a significant part in the unprecedented fragmentation of choices in 2024. British constituencies are large, and even those considered “safe” are more diverse than people assume. Every one will contain many voters keen to take advantage of the new choices made available to them. One way we can see this is by looking at the average vote shares going to third and fourth placed parties - by definition voters backing such parties are expressing their preference for a locally smaller party who will in most cases have little chance of winning.

In 2024, the average vote share for the third placed party rose to over 15%, while the average fourth place vote share rose to nearly 8%, an all time high. Add those together and nearly a quarter of voters, on average, were backing parties not in the top two locally - and with at least five candidates in every seat, plenty more voters will have backed candidates placing even lower.

Figure 4: Average third party and fourth party vote shares in 2024 election

Here’s one statistic which illustrates the powerful impact of all these extra choices on local election outcomes: Nineteen MPs have been returned to Parliament under 30% of the local vote in all the general elections since 1945 - and more than half of these MPs serve in the current Parliament.

These nine include Terry Jermy, the Labour candidate who overturned a 51 point majority to defeat former Prime Minister Liz Truss in South West Norfolk, achieving a record Tory to Labour swing despite increasing Labour’s vote share by only 8 points. Jermy emerged victorious with just 26.7% of the vote, the lowest ever won by a winning Labour MP, from a true Royal Rumble featuring a near perfect three way split between Labour (27%), Conservatives (25%) and Reform (22%); and a major local plot twist worthy of the WWE, as James Bagge, a septuagenarian member of the “Turnip Taliban” - disgruntled local former Conservatives who had often been opposing Liz Truss since she was imposed on the seat in 2009 - entered the political ring and took 14% of the vote.4

South West Norfolk 2024 election illustrated

South West Norfolk was a spectacular example, but it was far from an outlier. The number of seats across Britain where the local winner prevailed with 35% of the vote or less rocketed from just a single seat in 2019 to 99 seats in 2024, as fragmented voting enabled by more choices on the ballot paper drastically lowered the bar for victory in many seats.

The new normal? Messier contests, more fragile victories, greater volatility

British voters had more choice than ever in 2024, and this trend is unlikely to reverse. Party systems everywhere are becoming more fragmented, and in Europe’s more proportional systems it is not unusual for ten or more parties to achieve representation in the national legislature. The smaller parties who have risen to record heights in July’s election - the Greens and ReformUK - occupy a clear ideological and social niche , and similar parties have been fixtures of most European party systems for decades. First past the post could not postpone their emergence in Britain forever, and now they have the organisational capacity to stand almost everywhere, they are likely here to stay. The populist-left independents who mobilised discontent over Gaza could yet evolve into another lasting fixture of the party system too, given their distinctive appeal to a geographically concentrated Muslim electorate.

Greater choice, then, is likely here to stay. And with many voters eager to exercise such choice, the two largest parties are unlikely to dominate voting in coming elections in the way they did for many decades. Yet both parties still enjoy (for now) a big structural advantage under first past the post, and remain in pole position as the parties likely to lead governments. In a system where coming first is all that matters for winning seats, the aggregate impact of all these extra votes going to parties finishing third or below will be to reduce the overall vote share needed for the biggest parties to prevail. Labour won a massive majority with less than 35% of the vote in part because millions of votes were “wasted” on Green, ReformUK and other candidates with no prospect of winning. When choices were limited for most voters, a winning party typically needed over 40% of the vote to secure a Commons majority. If a big slice of the vote goes to smaller parties in every seat, 35% may be the new yardstick for victory - or even less if a winning party distributes its support efficiently across seats.

Such Commons majorities may, however, become less secure, as they will typically be built on narrower constituency victories. The appeal of the new choices is not randomly distributed and, as we shall see in the next post, the rise of new options has tended to hit both the Conservatives and Labour hardest in their traditional heartlands. Voters in neglected “safe seats” have particularly strong incentives to exercise new options - doing so is a low risk way to express discontent or attract more attention from the locally dominant party - and now such options are established, such behaviour may spread. The 2024 majorities in Labour’s safest seats are dramatically lower than those in 1997, when the party achieved a similar overall seat total. With more choice, fewer places can be taken for granted.

The distinctive geography of the Greens, ReformUK and the independents also means rising choice has translated into greater diversity in electoral battlegrounds going forward, with a wider variety coming first and second in 2024. The number of seats where Labour and the Tories held the top two spots fell from 462 (73% of the GB total) in 2019 to 306 (48%) in 2024. More than half the contests next time will feature an incumbent or strongest local challenger from outside the “big two”. This, in turn, will change the incentives voters face and the strategies parties devise in ways likely to further entrench diversity and fragmentation.

The new high choice environment may also result in a new class of “super-fragmented” seats where votes are spread evenly over three or more parties, creating volatile contests with multiple winning strategies open to several parties, along with complicated calculations for local voters. There were over 20 seats in 2024 where the gap between first and third place was less than 10 points, and over 80 seats where the gap was under 15 points. In all of these seats, the third place party could make a credible claim to being locally competitive. Future outcomes in such seats will depend both on flows of votes between the three big contenders and on the ability of each larger to squeeze votes from the smaller parties placing fourth or below. National polling will often be of little use for projecting such outcomes and even MRP modelling will struggle with such local complexities.

The combination of more fragmented votes, more fragile majorities, and complicated, shifting local tactical contexts will also make for more volatility from one election to the next. We have this year seen one government with a large majority collapse and be replaced by another with an even larger majority. Big shifts in the composition of the Commons may become given how choice and fragmentation interact with first past the post. Both Labour and the Conservatives are likely to build “jenga tower” majorities in the future - tall but unstable, with fewer safe seats to fall back on if the national tide goes out.

Voter fragmentation therefore erodes the case for the current electoral system in two ways. Millions of voters now backing smaller parties who are heavily penalised by the current electoral system, and greatly under-represented in the House of Commons. But the new fragmentation may also weaken one supposed advantage of FPP - that it delivers stable, one party majority government. The fragile “jenga towers” delivered by a fragmented electorate are not like the stable majority governments of the past - hundreds of governing party MPs risk swept in on narrow victories could be swiftly swept out again at the turning of the electoral tide. Governments whose majorities rest on inexperienced MPs with insecure majorities are likely to be more divided and less effective. This may in turn start to raise questions about the long term viability of an electoral system which marginalises smaller parties yet also destabilises the larger ones. The demand for more diversity in politics which is already evident on local ballot papers and in constituency results may eventually need to be met at Westminster too.

Some of these votes will come from previous abstainers, a complication I’m setting aside here. While this reduces the impact on the biggest parties somewhat, no big new party mobilises exclusively (or even mainly) from former non-voters, who are very hard to engage, so there is always some diversion of votes from existing large parties.

In 2010, Martin Bland changed his name by deed poll to “We Beat The Scum 1-0” and stood for election in Leeds Central, in order to write Leeds United’s FA Cup triumph over Manchester United that year and won the backing 155 voters, presumably Leeds fans eager to recognise this rare and unusual event (Leeds, a smaller and more financially challenged club, have not beaten Manchester United since).

Omilana, who told ITV News he "took it personally when Rishi Sunak decided to send young people to the front lines” did not only stand in Sunak’s seat. His name also appeared on the ballot in 10 other constituencies - allegedly fans willing to change their names by deed poll (and post a £500 deposit) to support their YouTube hero. By this metric, Niko Omilana is 11 times more popular than Leeds United.

The Greens also took 4.1% of the vote in Truss’s seat, 0.8% backed the Monster Raving Loony Party’s “Earl Elvis of East Anglia”, 0.4% backed the right wing splinter Heritage Party, and 0.2% backed the Communist party, the Communists’ worst showing in the 14 seats they stood. Even Liz Truss couldn’t convince Norfolk of the virtues of Communism.

To prove how closely I've read this excellent piece: you have a double "been been" part way through, Rob.

Whichever of the big parties goes for PR first, will regain the long term initiative. This fragmentation and FPTP is blatantly unfair and wasteful of votes.