Local elections preview

Things to watch out for as a fragmented England votes

Spring is here, the sun is out, and that can mean only one thing: local elections are upon us once again. Today’s contests in England are the first electoral test for the new Labour government who haven’t had the easiest time of it since the loveless landslide of last July, when ruthless electoral efficiency enabled Labour to triumph over all comers in a fragmented contest. Fragmentation will be one of the big themes again this weekend. These will be the first ever English local election contests to feature nationwide five party competition, and with the polls showing both traditional governing parties down in the polls, winning less than half of the vote between them, with gains for both Reform on the right and the Lib Dems and Greens on the left, we may be in for a very messy set of results. And, to top it off, we have the first by-election contest of the new government too, with Labour defending the apparently safe seat of Runcorn and Helsby from the rising forces of Farage.

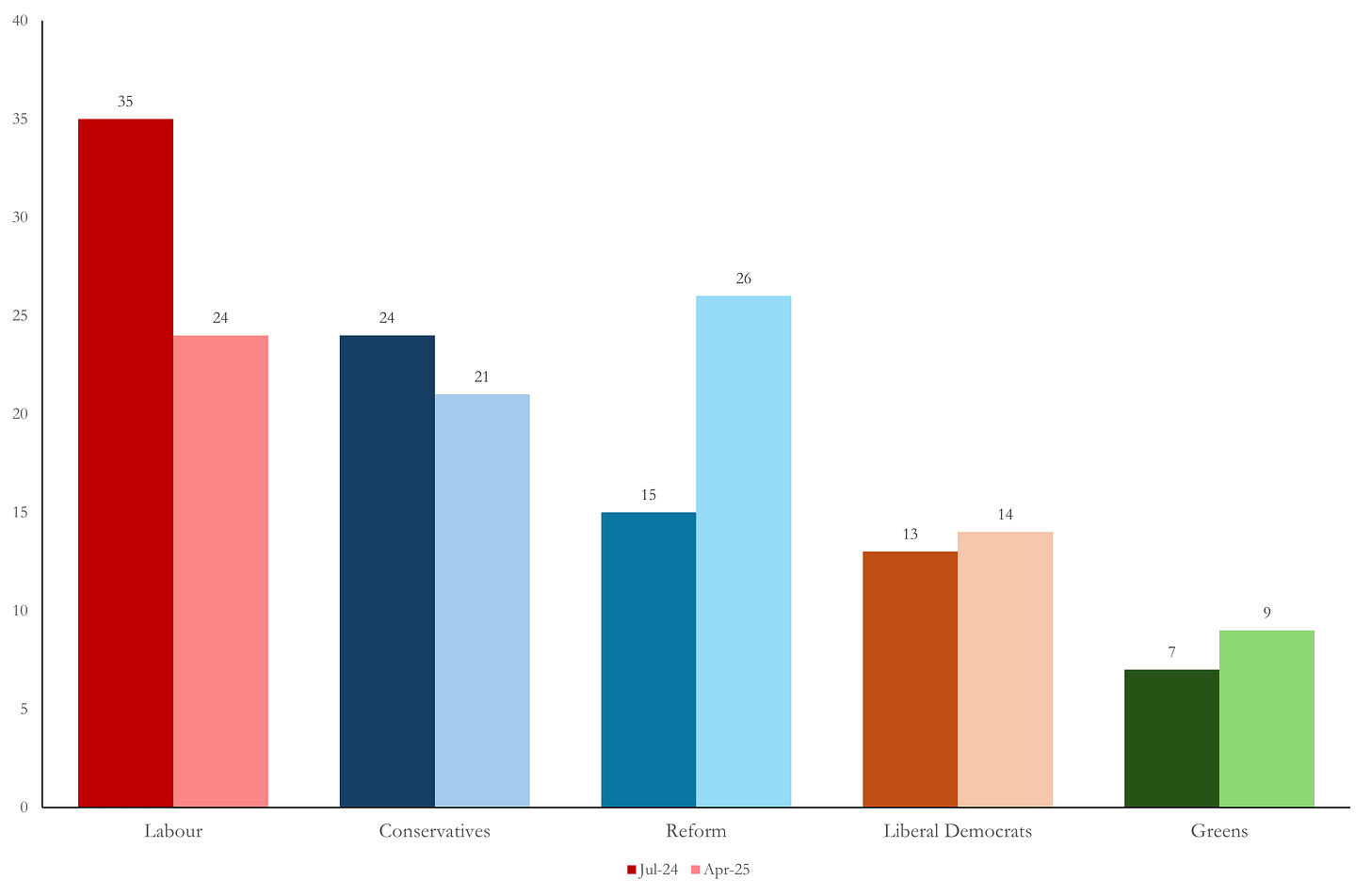

Poll averages, April 2025 vs July 2024 GB election result

Average of latest polls from FindOutNow, YouGov, MoreInCommon, Opinium, Techne and FocalData (light bars). Election result in GB July 2024 (dark bars)

Who will win in Runcorn and what will it mean?

The results this week will be split unevenly over two periods, with the Runcorn by-election, four mayoral contests and a smattering of local council wards mostly in very Leave bits of the Midlands and North counting overnight, then the main wave of local results along with two combined authority mayors declaring at more civilised time across Friday morning and afternoon.

The headline overnight fixture, for journalists and psephological insomniacs alike, will be the Runcorn by-election. Keir Starmer failed his first electoral test as opposition leading, losing the formerly safe Labour seat of Hartlepool exactly four years ago, a humiliating defeat which provoked the first and so far only serious threat to his leadership. Defeat for Starmer in another safe Labour seat would immediately become the headline story emerging from these contests, demonstrating that Labour’s polling weakness is converting into electoral vulnerability, while also providing ReformUK with their first by-election win. A win for Reform would make history in another respect - despite regularly talking about “parking his tanks on Labour’s lawn”, none of Farage’s various parties have ever defeated a Labour MP in a Westminster contest. But how likely is it?

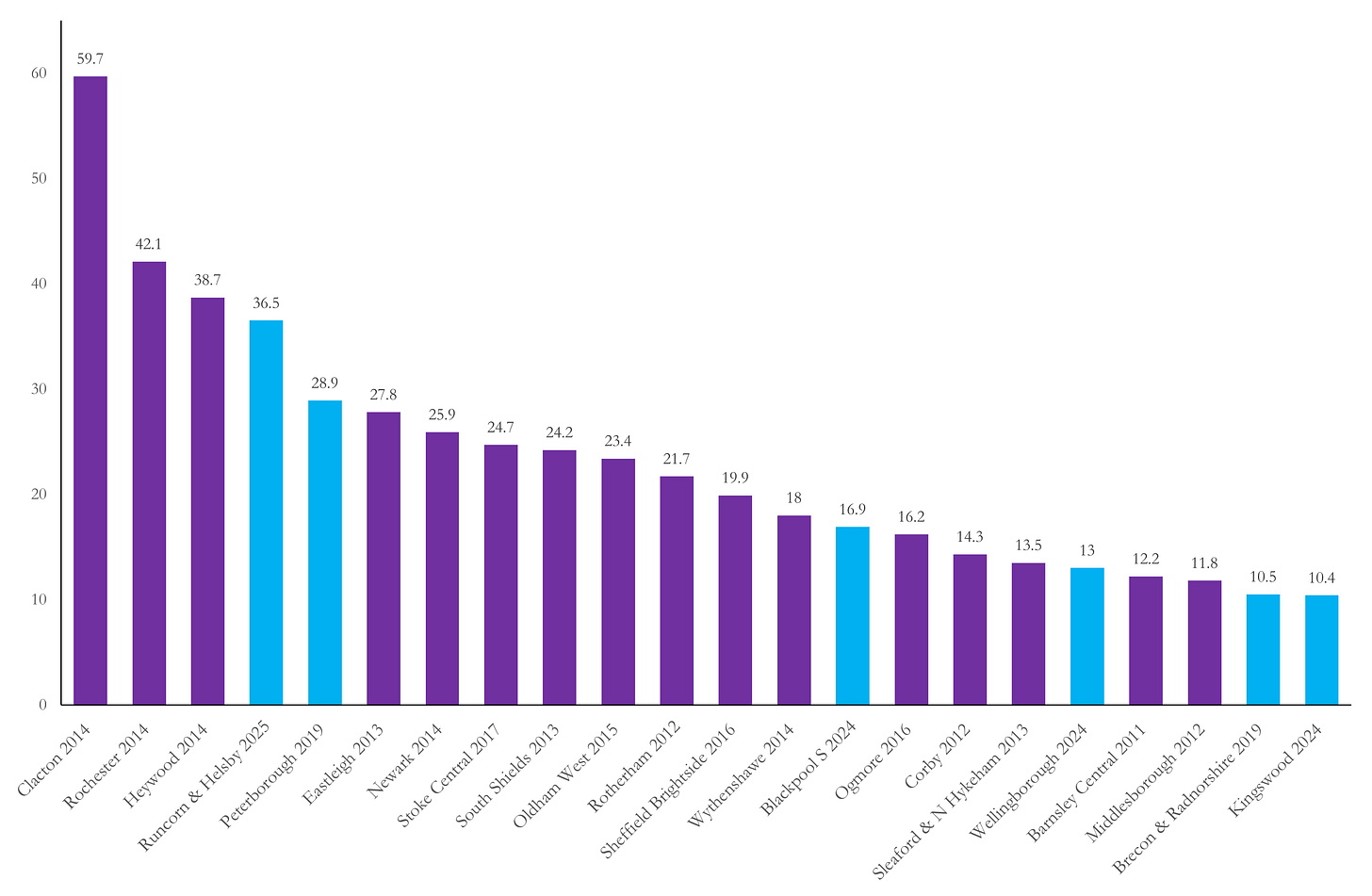

The swing required in Runcorn was topped many times in the last Parliament

Labour start with a 35 point majority in Runcorn and Helsby having taken more than half of the vote there last July, meaning a 17 point Labour to Reform swing is needed to take the seat. While that sounds like a heavy lift, swings larger than this became almost routine in the second half of the last Parliament, as the graph above illustrates. The Lib Dems took four seats from the Tories with swings of 25 points or more, Labour made six gains with swings above 20 points, and George Galloway took Rochdale on a colossal 42 points swing in February last year. In such volatile times, a 17 point swing against an unpopular government looks perfectly achievable. Indeed, the average swing Labour achieved in Conservative-Labour contests between 2022 and May 2024 was 15 points, not much less than Reform need now.

Reform’s best by-election performance to date came in Peterborough in 2019 when the party, then known as the Brexit Party, secured 28.9% and came second to the incumbent Labour party in a by-election held immediately after a European Parliament election where the Brexit Party came first overall. Reform will likely need to do substantially better than this to win in Runcorn - on a straight swing from Labour the party will most likely need to win 35% plus to take the seat. While this would be Reform’s best ever performance, Nigel Farage and friends have done better than this competing under UKIP colours - former Conservative MP Douglas Carswell won nearly 60% in Clacton (the seat now represented by Farage himself) in the by-election Carswell triggered after defecting to UKIP in 2014, former Tory MP Mark Reckless won 42% in Rochester & Strood after following Carswell into UKIP, while John Bickley won 39% in Heywood & Middleton, to date the best performance by a Farage party in a Labour held seat. If Reform top that in Runcorn they will almost certainly win.

UKIP and Reform by-election vote shares, and estimated Reform vote in Runcorn on a 17 point swing

Whether Reform do break through may come down to two factors - fragmentation and organisation. The Conservatives polled 16% in Runcorn and Helsby in 2024, only narrowly behind Reform. These should in theory be low hanging fruit for Farage, given Conservatives are typically more Reform curious than Labour voters. A tactical squeeze of third placed Tories would make a Reform win a lot easier and worry other Labour MPs who currently benefit from divided right wing opponents. But it is not yet clear whether Conservative voters will be receptive to the tactical “vote Reform to get Labour out” message or whether, instead, they will reject the advances of a party aiming to displace the Conservatives as the main force on the right. Affection for the Conservatives may run deep among voters who stayed loyal to the party even in the dire circumstances of July 2024 - they may not be eager to hand a big win to the man who makes no secret of his desire to complete a hostile takeover of the right.

Fragmentation will also matter on the left. Nearly one voter in ten in Runcorn backed the Lib Dems or the Greens in 2024, and more progressive voters now face a conflict between their desire to express their unhappiness with the direction of the Labour government and their desire to avoid being represented by a Reform MP. Which force wins out among conflicted right and left voters may prove critical, and the strength of local party organisation may help tip the balance. Labour built a very impressive campaigning machine in the last Parliament, but inflicting defeats in opposition is a different task to averting them in government. Reform have made a lot of noise about their professionalisation efforts, but as yet these claims are untested, and even if they have money and activists, they have little experience to draw upon. While victory or defeat will determine the narrative, it is the pattern of voting and of turnout that will perhaps tell us more about the parties’ prospects going forward.

Will clear winners emerge in the combined authority mayoral contests?

Fragmented voting also looks to be a major theme in this week’s mayoral contests, with four large combined authorities electing mayors alongside two smaller, more homogenous local areas with directly elected leaders. Pollsters have been rather keener to take the temperature of these contests than was the case last year, with both MoreInCommon and YouGov polling all four large Mayoralties. Voting is deeply fragmented across these large and socially diverse combined authorities, which makes them exceptionally hard to predict.

Polling for the four combined authority mayoralties

Source: Average of YouGov and MoreInCommon Mayoral polls

Labour only won last time in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough thanks to the previous supplemental vote system, overtaking the Conservatives on second preference votes from smaller party supporters. They now look set to lose a contest under the new system that they might well have won under the old system - vindicating the Tory choice to switch system and underlining Labour’s strategic error in not swiftly switching back. Polls have former Conservative MP Paul Bristow well ahead, but on a vote share of barely over 30%, with Labour, the Lib Dems and Reform all getting around 20% and the Greens on 9%. Fragmentation and the electoral system may also play a crucial role in Hull and East Yorkshire, where this time it is Reform who have their noses ahead and may win a contest split four ways with less than a third of the vote.

If Cambridgeshire and Hull look messy, wait until you see the West of England, where just nine points separate five parties in the polls. The Greens and Labour are tied on 23% each, the Conservatives and Reform are slightly behind on 19 and 18% respectively, and the Lib Dems are in the mix on 14% too. This really is pure electoral chaos, and aside from making tactical voting more or less impossible, as there are no clear leaders to coalesce behind, it means whoever wins is likely to have an exceptionally weak mandate, winning little over 20% of those who have voted in a low turnout contest. Labour have high hopes for the mayoral model, but it may be hard for mayors elected with a third or a fifth of the vote in such chaotic contests to speak with much authority.

The only mayoralty which looks set to deliver a decisive outcome is Greater Lincolnshire, where former Conservative MP Andrea Jenkyns looks set to win decisively in one of the most Leave leaning patches of England. Directly elected mayors have emerged as influential voices in both Labour (Sadiq Khan, Andy Burnham and Steve Rotherham) and the Conservatives (Andy Street and Ben Houchen and, earlier, Boris Johnson) so it will be interesting to see what role Reform’s mayors play in a fractious party where Nigel Farage has generally been less than eager to share the spotlight or tolerate dissent, and where splits and departures have been a frequent occurrence. Electing mayors is one thing. Keeping them in the party may prove quite another.

Local elections: A new landscape emerges?

Friday will be a bloody day for Conservatives in local government. Most of the seats up this time are in county councils which tend to lean Tory, and were last contested in May 2021 when the Conservatives were at the peak of the vaccine bounce and Reform barely stood any candidates. The polling shift since then has been brutal, with the Conservatives losing almost half of their support, falling from 41% to 21%, while Labour are also now well down, falling from 37% to 24%. Reform, who were so weak in the spring of 2021 that some pollsters didn’t even register a separate figure for them, have risen from 2% to 26%, but there have also been gains for both smaller parties on the left of the spectrum, with Lib Dem support doubling from 7 to 14% and the Greens nearly doubling from 5 to 9%.

Vibe shift: Polling averages in April 2021 and April 2025

Source: Average of final polls before May 2021 local elections from YouGov, PanelBase, Redfield & Wilton, Savanta ComRes, Focal Data, Opinium and Survation. April 2025 poll average from same sources as before

While the polls show a huge shift away from both governing parties since 2021, the Tories dominant position when these seats were last contested leaves them much more heavily exposed this time. Shifts in the patterns of candidature will magnify the effect. Only a few dozen Reform candidates stood last time, so even if many voters wanted to back a local Farage candidate this was not an option. Reform are now standing a full slate of candidates across the length and breadth of England - something neither they nor UKIP have ever done before. The Greens and the Liberal Democrats are also putting up much bigger slates this year, meaning four or five party competition in far more wards than before. Electoral chaos theory has arrived in local elections. With voters splitting across five national parties, it will be harder than ever to make sense of the resulting electoral landscape. I will take a look at some of the big trends emerging from this week’s results in a future post, but here are five things to watch out for as the results come in.

(1)How low with the Tory vote go?

However we measure it this looks set to be a historically awful night for Badenoch’s Conservatives, who continue to go backwards after their worst ever election result last summer. The Tories are defending nearly a thousand of the 1,600 seats up, and can expect to lose hundreds of them, many directly to Reform. While a Reform win in Runcorn is a headache for Labour, a Reform advance across a broad front in local elections poses an existential threat to the Conservatives, potentially pushing them into third place behind the Liberal Democrats in local government, confirming their third place status in polling, and raising the chances they will be displaced as the official opposition in a future general election.

A lot of the media attention will focus on how many seats the Conservatives lose, but the more important metric is votes cast. Last year saw the Conservatives fall to 25% in the BBC’s Projected National Share (PNS)1, equalling their worst ever showing on this measure. If they fall substantially below this, it will provide clear evidence that their electoral crisis is worsening in opposition, and raise questions about whether a change in leadership may be needed to turn around their fortunes.

(2) How low will the Labour vote go, and how much will Reform hurt them?

Downing Street will be relived that the electoral map this time features so little red terrain. If Labour manage to hold Runcorn and the two smaller mayoralties reporting overnight, the heat will largely be off the government despite a steep fall in the polls since the general election (though trouble in Doncaster, the one metro borough voting today, will cause some headache’s given this is the home turf of Ed Miliband). But we can still track changing Labour fortunes even where the party lacks incumbents.

Labour scored 35% on the BBC’s PNS measure last May, an outcome which closely matched their general election result two months later. Their are very likely to do a lot worse this year, but the scale of the fall is worth watching. Labour’s worst result ever on the BBC’s PNS measure was 20% in 2009, in the wake of the financial crisis, while their worst result under Corbyn’s leadership in opposition was 29% in 2017 and 2019. A fall below Corbyn levels of support would be a bruising blow for the government after less than a year in office - the last Labour government posted scores in the high 30s for two successive years. - while a decline towards post-financial crisis lows would signal a major electoral crisis for the government.

With hundreds of Reform candidates standing for the first time in Labour areas as well as Conservative ones, these local elections will also give us a sense of the degree to which Reform actually deliver on Nigel Farage’s claim to be parking his tanks on Labour’s lawn. National polling suggests Conservative voters are more Reform curious than Labour ones, but the Reform effect could vary a lot depending on local conditions - and Reform’s advance in places like Doncaster and County Durham will be watched closely and nervously by Labour MPs and electoral strategists.

(3) Will Reform match their polling, and beat UKIP’s best showing?

While Reform have made much of their growing professionalism, and have already bested UKIP in fielding a full slate of candidates, their capacity to engage and mobilise voters in low turnout elections remains untested, and it remains possible that some polls are overstating Farage’s rise. UKIP’s best ever performance in local elections came in a similar shire England set of county council elections in 2013, when they scored 23% on the PNS (not coincidentally, this was also the Conservatives’ worst ever year). Reform are doing better in the polls now than UKIP were then, and are standing a lot more candidates, so they should be well placed to beat this outcome. A failure to do so would suggest either the party is underperforming its polls or that it still has work to do building its campaigning organisation.

(4) Will the gold and green tides continue to rise unnoticed?

Both the Liberal Democrats and the Greens have made hundreds of seat gains in recent rounds of local elections, quietly accumulating local strongholds while flying below the radar in the national political conversation. These gains presaged major advances in Westminster elections for both parties last year, as both parties cashed in on local credibility and organisation. With both parties rising in the polls, their advance in local elections could again have significant implications for future Westminster contests. The Liberal Democrats are looking to take advantage of continued Tory weakness and consolidate their status as Home Counties Hegemons. Big gains in the wealthier, more Remainy shires such as Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire and in the party’s traditional South West heartland areas such as Devon and Cornwall will boost the third party’s hopes of consolidating their huge advance from last July and perhaps expanding on it further - the party only need a few dozen more Conservative seats to potentially become the official opposition.

With only four Westminster seats the Greens are a long way from official opposition status, and this years local contests do not feature many of the diverse, graduate heavy urban areas where the party did well last July. But the Greens are rising in the polls, and standing a record slate of candidates, and two of last year’s general election gains were built on local election advances in traditionally Tory areas. So it will be worth watching their performances closely to see if new Green islands are emerging in the shire seas of blue, gold and turquoise.

(5) What will the electoral map look like after this week?

It is clear from even a very brief run through of the parties’ prospects that the rise of five party politics is going to reshape the electoral map once again. But what sort of map will emerge, and what sort of contests will we have going forward? With each party having distinct social and geographical bases of support, England may form into an electoral patchwork quilt, with different parties coming to the fore in different areas. Lincolnshire may be broadly Tory-Reform, County Durham Labour-Reform, Oxfordshire Lib Dem-Tory, Cornwall Lib Dem-Reform and so on. And these are just the broad brush strokes - a chaotic contest may mean a fractal map, with distinctive micro-climates in individual wards even in areas with a distinct overall pattern of competition.

With smaller parties standing so many new candidates, and far more wards featuring four, five or more names on the ballot, there could also be a dramatic rise in three, four or even five cornered ward contests, micro-versions of the West of England free-for-all. And with wards having small electorates and low turnouts, such contests could come down to handfuls of votes, while their winners could be returned to represent a ward despite winning the support of less than one in ten local residents.

The final point to ponder is how parties and voters will react to this much changed map going forward. Will narrow third or fourth place finishes push some parties out of the running next time, as voters seek to coordinate behind the best placed local challengers? Will parties similarly focus their efforts on the patches of the multicoloured electoral quilt where their prospects look brightest, thus entrenching and exaggerating variations in competition pattern from one area to the next? How will local councils accommodate new and unpredictable multi-party coalitions? And will volatile and unpredictable results spark new conversations among voters, councillors and parties about whether a first past the post electoral system makes sense in a world of fragmented, multi-party competition at all levels of politics? Whatever happens this week, one thing seems certain - the turn away from traditional two party politics is accelerating, taking us into uncharted territory at all levels of politics.

PS: This is the first Swingometer for a while - I have had to take a sabbatical from blog posts to work on “The British General Election of 2024”, which will be published with Palgrave later this year, and will be jam packed with historical and psephological analysis of every aspect of a fascinating election. More news on this soon!

For more on the PNS and how it is calculated (and why this year is a particularly tricky calculation), see this excellent article from Stephen Fisher: https://electionsetc.com/2025/05/01/understanding-the-local-elections-projected-national-share-pns-in-2025/#more-2898

Good to have you back, was bit quiet on that area

Un análisis claro, riguroso y argumentado.