Local elections: The Big Preview

Part 1: The lay of the land

The final big test before the general election is upon us, with a smorgasbord of electoral contests this Thursday, including a Westminster by-election; the election of ten mayors in many of England’s largest cities, including the capital; the election of all members of the London Assembly; elections to some or all seats on 107 local councils, and the election of 37 Police and Crime Commissioners in England and Wales. In this special three part Swingometer Big Preview, I’ll take you through what to look out for and what to expect from a big and messy mass of election battles. This first post takes a look at the big picture before we get deep into the weeds of individual contests in the posts to follow.

I asked the AI to depict the local elections as a WWE royal rumble style event and this is what it spat out

The national context going into these local elections is very good for Labour and very bad for the Conservatives. Labour has a lead of around twenty points over the Conservatives in national polling and have had that lead for the best part of two years. Seat prediction models are routinely estimating a landslide for Labour at the next general election, and so far everything which Rishi Sunak has tried has failed to reverse this. If anything, things seem to be getting worse for the Conservatives, with Sunak’s approvals and vote intention poll numbers still falling, and just last week another MP defecting – this time to Labour (the second Tory to Labour defection of this Parliament).

Most of these local elections were also last held in 2021, when a Boris Johnson led government was riding high in the polls in what we now know was a “vaccine bounce”. The party has fallen a long way since, and is currently polling less than half the level recorded in April 2021.

At those local elections in 2021, the Conservatives held a ten-point lead over Labour in the Projected National Shares calculated by the BBC. The Conservatives won the Hartlepool parliamentary by-election on the day of the 2021 local elections and Johnson was suggesting he was planning for a decade in No. 10.

If Labour’s current poll lead is mirrored on election day this year, this will be a plunge from the heights of 2021, with the Conservatives certain to lose hundreds of councillors and some councils, as well as losing a Red Wall by-election in Blackpool South.

The narrative of this local election cycle could therefore end up being a mirror image of 2021 – whereas last time the Conservatives started with a headline grabbing Westminster by-election win, followed this up with big gains in councils across England, and finished with an iconic victory in the hotly contested West Midlands Mayoralty, this year could involve the same pattern unfolding but with Labour victories at every stage.

That said, around a third (36 of 107) of the councils up for election in 2024 last held elections in either 2019, 2022 or 2023 because of boundary changes. 22 of the 107 councils having elections have new boundaries. A further 14 councils have elections on boundaries which were created since 2021 (or in the case of Dorset, 2019). Whilst the change is minimal in many wards, plenty of wards will see substantial boundary change, which makes like for like comparison impossible. Wins and losses are tallied based on estimated notional results.

These changes matter because a notional Conservative ‘loss’ of a council seat in areas with boundary changes will be a loss from 2019 or 2022 or 2023, when the national context differed from that in 2021. Boundary changes may therefore dampen the effects of a very good Labour night. We are comparing those councils against elections where Labour was already leading in the national vote share (2022 and 2023), albeit by less than they are now. On the other hand, when extensive boundary changes result in “all up”1elections it may mean more seats are in play for the Conservatives to lose and Labour to gain.

Targets for the big Westminster parties

The media coverage of the local elections will focus on seats and councils gained and lost by each party. This is, however, a confusing metric as the number of seats up changes drastically from one year to the next, as does the mix of places. Two factors limit the scope for Labour gains and Conservative losses this year compared with last: there are far fewer seats up for election in this year’s contest than last, and most of the councils with elections this year are already Labour controlled. On the other hand, these local elections were last fought at a high water mark for the Conservatives, so they could easily lose half or more of the nearly 1,000 seats they area defending. Labour will hope to take the lion’s share of these and post 300 plus gains, the Liberal Democrats will hope for triple digit gains too, with a more modest overall advance for the Greens.

The BBC’s Projected National Share, which models what would have happened if everyone had voted in local elections, provides a more consistent yardstick of the parties’ ebbs and flows.2 The table below shows the BBC Projected National Share (PNS) for each cycle since 2019, the party leading on PNS in each year, together with the national lead in the polling average at the time of the local election.

Projected national shares, party leads and polling leads 2019-2023

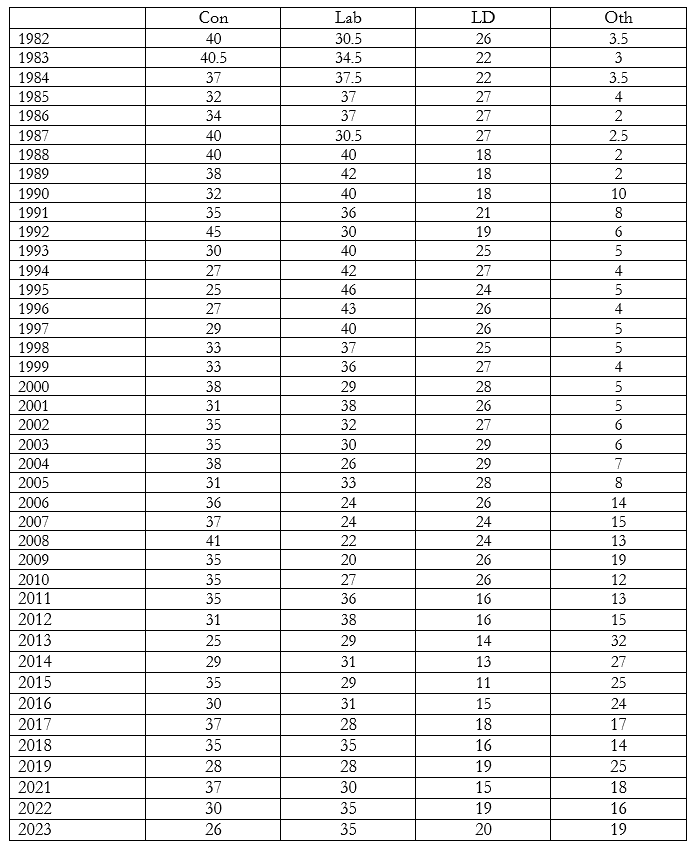

The lowest PNS ever recorded by Conservatives is 25%, in 2013 and earlier in 1995. They narrowly avoided hitting this floor last year, when they posted 26%, but they go into this years contests in an even worse polling position, around 20 points behind in the polling averages. A PNS share below 25% would be the lowest ever recorded since the BBC started calculating these figures in 1982.

The first target for Labour is to go above 35% - this is the highest PNS recorded by both Keir Starmer (twice – in 2022 and 2023) and by Jeremy Corbyn (in 2018). This should be easily achievable given Labour’s bigger poll lead this year. The next target is 38% - the highest PNS recorded by Labour in this period of opposition, achieved by Ed Miliband in 2012. The ultimate target for Starmer and Labour would be 46%, Labour’s all time high PNS figure recorded under Tony Blair in 1995. However, with voting in local elections now much more fragmented, this mark is likely out of reach. Anything close to 40% will be a dominant performance.

The Liberal Democrats will be aiming for 24% - they never fell below this level of support on PNS between 1993 and 2010, and have never risen back to this level since. Getting back to around a quarter of projected national share would show they are returning to pre-Coalition levels of vitality in local government.

Reform and the Greens

These elections provide us with the first national assessment of the performance of Reform UK. Thus far, the party has done poorly in parliamentary elections and has barely stood in local contests. However, even the bigger Reform slate this year is only 329 candidates, or around 12% of all seats contested on the night, so this is a pretty patchy ‘national’ assessment. Reform are, for example, standing no candidates at all in many areas with high Leave votes where UKIP did well in the early 2010s. The party may gain a handful of seats at the expense of either Labour or the Conservatives, but with such a small slate it is certainly not going to match the UKIP performances of 2013-15. The bigger impact from Reform may be indirect: its presence or absence may have a big effect on Tory fortunes in individual wards and councils.

The Greens have made record gains in the last couple of years and are now stronger than ever before in local elections, standing candidates across the length and breadth of England and winning hundreds of seats. The number one Green target this time is Bristol City council, where they are hoping to take overall control. The Greens are also targeting Bristol in the general election, so Bristol has become a key marker for their performance. The party will also look to build where it is already strong in councils such as Norwich, Sheffield, Stroud, Worcester, Burnley, Oxford and Reigate & Banstead. While the Greens were once concentrated in urban progressive areas, they are becoming a more diverse party as they spread – they are now the main local opposition to the Conservatives on some very blue councils.

Five questions for this year’s locals

Local elections are low turnout elections and show consistent systematic differences in voting patterns – with the Liberal Democrats, Greens and others all regularly doing much better in local elections than in general election contests. We can’t therefore infer too much about general election prospects from local election performance. However, these contests will shed light on several important questions:

1. How big is Labour’s advance in the ‘Red Wall’? There are plenty of elections taking place in parts of the country which Labour lost to the Conservatives in 2019. Labour did poorly in such areas when most of these seats were last up, but has advanced strongly in the last couple of years. They will want to register big gains to demonstrate they are on track for a Commons majority. Elections of note here include Bolton, Burnley, Bury, Dudley, Walsall, Hartlepool, the East Midlands and Tees Valley mayoral races, and Wigan.

2. Is Labour struggling in councils with large Muslim communities? Recent months have seen some polling to suggest that Labour is losing a little support amongst Muslim voters over its stance on Gaza. Senior Labour figures are concerned at this possibility, and these elections take place in many areas with high concentrations of Muslim voters, including several areas where multiple Labour councillors have resigned over the national party’s stance on Gaza Elections to watch here are the West Midlands mayoralty, Blackburn with Darwen, Bolton, Burnley, Coventry, Dudley, Oldham, Rochdale, Rotherham, Walsall. It will be worth watching both vote patterns and turnout – one impact from Gaza is Muslim voters alienated by Labour but unwilling to back other parties may opt to abstain.

3. How much tactical voting is going on, and who is benefitting? In the last couple of local election cycles, there has been growing evidence of voters coalescing behind whichever challenger party has the best chance to defeat Conservative incumbents. This has magnified Tory seat losses in local contests, and could have the same impact in the Westminster contests to come In many Southern councils the Lib Dems have gained from tactical squeezes on Labour support. In the Midlands and the North we may see Labour benefit from Lib Dem and Green tactical votes. The Greens may also benefit from Labour and Lib Dem tactical votes in the growing number of wards where they have managed to establish themselves, and in their top target: Bristol council.

4. Is Reform UK a real threat or a paper tiger? Reform is standing in only a small portion of the seats being contested but are they making progress at the Conservatives or Labour’s expense…..and, if so, where? Will they take seats directly from the other parties or achieve a large enough vote to make it easier for Labour or other parties to defeat the Conservatives? Will they win substantial vote shares in safe Labour wards in the ‘Red Wall’, in places which UKIP previously did well? Elections to follow here are the East Midlands mayoralty which includes Ashfield constituency, Barnsley, Wickford North ward in Basildon, Little Lever ward in Bolton, the Gornal wards in Dudley, Cannock Chase, Castle Point, Hartlepool, St Oswald’s ward in Hyndburn, North East Lincolnshire, Sitwell and Dinnington wards in Rotherham, Brownhills ward in Walsall.

5. Will Tory voters stay at home? Look for Conservative turnout relative to the last local elections in the safest Tory wards. If turnout is down, it may point to disaffected Conservative voters choosing to stay at home rather than vote for another party. If turnout is up, and the Conservative vote is down, then it may indicate Conservative voters are switching directly to local opponent parties, at least in this election.

A rough timetable of important contests

These local contests are unusually strung out, with counts taking place from Thursday night through until late Saturday or even Sunday in a few places. This further complicates the task of understanding the outcome, with early results likely to set the tone of discussions even if later reporting councils paint a different picture. Here is timetable of expected declaration times from the Press Association for some of the important contests to watch

Press Association expected declaration times (contests other than council elections in bold)

As the table above makes clear, this is a big and messy electoral battlefield. In the next two posts, I’ll take you through everything that’s up this year and fill in what’s at stake and what to watch for, starting tomorrow with all the non-council contests. One more little gift to close for the true election nerds - here’s a table of the BBC’s Projected National Shares in every local election since 1982.3 Enjoy!

BBC Projected National Shares since 1982

Note: There was an error in the PNS figures reported for 2021 when this article was first published. This has now been corrected - my thanks to Luke Tryl for flagging this error to me.

An “all up” or “all out” election is where all the councillors on the council are up for re-election. Typically, only a third of councillors are up for re-election each year.

For a comprehensive guide to the Projected National Share, see this explained from Stephen Fisher: https://electionsetc.com/2023/05/03/understanding-the-local-elections-projected-national-share-pns-in-2023/

With thanks to Stephen Fisher, who originally posted this table (or nearly all of it) on his blog a few years ago.

Interesting piece Rob. Here is another view: https://theleftlane2024.substack.com/p/remembering-the-election-of-1885 Alan Story/THE LEFT LANE