This piece was originally written in 2018. As the new Labour government elected in July is committed to pursuing a package of reforms to elections and the democratic process, with the King’s speech promising action to “strengthen the integrity of elections and encourage wide participation in the democratic process”, this seemed an opportune moment to update and report an examination of the case for extending the franchise to millions of settled migrants who currently contribute to Britain’s economy and society, and have committed to living here long term, yet have no voice in national elections - despite overwhelming public support for extending full voting rights to settled migrants.

One common argument used in recent campaigns to lower the voting age to 16 is that Britain’s youngest citizens have the strongest interest in the long term decisions taken by government, yet currently have no say in the choices that are made.1 This argument has become particularly popular since the EU referendum, where very large age differences in choices emerged, which have persisted in all of the three post-Brexit general elections.

Yet there is a far larger group of British residents with an equally strong stake in the consequences of EU referendum and since which is nearly completely disenfranchised in national elections: long term settled migrants. It is both puzzling and concerning that the political rights of several million British residents who have made this country their long term home have barely featured in debates about reform of the franchise before or after the EU referendum. It is about time that they did.

The general rights of EU citizens - who are, as we shall see, the largest group of settled migrants without full political rights - were, of course, a major bone of contention throughout the Brexit negotiation process — with the British government (eventually) agreeing the principle of guaranteed rights, yet dragging out the process of defining how these would be administered and guaranteed after Brexit. The British government eventually agreed and set up a large scale scheme for registering EU migrants and securing their rights - to date there are 5.7 million individuals have received a grant of status under the scheme. The rights extended to such settled EU migrants do not, however, include the right to vote in general elections, even though the scheme itself is a powerful example of the central role the British government now plays in determining their rights and protecting their interests.

The debates over the settlement scheme, and indeed over Brexit in general, might have proceeded differently if MPs in Parliament had to worry about the votes of frustrated and anxious EU migrants — their large numbers and unusually even spread across the country would make them an important electorate in very many seats. Yet MPs could rest easy, then and now, because the vast majority of EU residents — including those here for decades — have no voting rights at all in British elections. They get no such rights as EU citizens and while they could secure such rights by taking out British citizenship, most have not done so.

Citizenship acquisition rates among the largest settled migrant groups, 2021 (EU countries highlighted in blue)

Source: Annual Population Survey 2020-21

There is a little known but hugely consequential inequality in the political rights of migrants. Citizens of Commonwealth countries such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nigeria, have the right to vote in general elections from the moment they take up residence in Britain, while citizens from everywhere else in the world tend to acquire British citizenship at high rates. The biggest losers from the current rules on migration, citizenship and voting rights are the millions of EU citizens resident in Britain, often for decades, but never able to cast a Westminster ballot.2 And while EU migrants are particularly reluctant to take out British citizenship, hundreds of thousands of migrants from other non-Commonwealth origin countries such as the United States, China or the Philippines also do not have British citizenship and lack general election voting rights, even if they have lived here for decades.

The low citizenship uptake rates of EU migrants is striking. Only one of the largest EU migrant communities had high rates of British citizenship as of 2021 (when the data series I have used was discontinued) — and that is a special case. Nearly two thirds of German born migrants to Britain have British citizenship — but many of these are the children of British servicemen who were serving on armed forces bases in Germany. After this the next highest figure is for Ireland — one in five Irish migrants has British citizenship. But Ireland is an exception in a different way, as all Irish citizens resident in Britain have, like Commonwealth citizens, the right to vote in British general elections from the moment they arrive.

Population and voting power of five largest Commonwealth and non-Commonwealth migrant populations (excluding the special cases of Ireland and Germany)

Source: Annual Population Survey 2020-21

Citizenship rates for the rest of the EU migrant communities are very low — less than one in twenty of the Poles and Romanians living in Britain has British citizenship, around one in eight French born residents have it, and only around one in ten of the Italian, Spanish and Portugese born migrant communities. As a result, EU residents in Britain are practically voiceless in British general elections — 680,000 Polish born residents have less electoral power between them than the 70,000 strong Malaysian community; the combined electoral voice of the large French, Spanish, Portugese and Lithuanian born communities is weaker than that of the far smaller Ghanian born community.

One likely reason for this from the point of view of the migrants themselves is fairly clear — EU residents came to Britain expecting their political and social rights to be guaranteed as part of Britain’s EU membership, which most assumed would be permanent. Migrants from other parts of the world typically faced stringent rules and limits from the British Home Office from arrival, so had a stronger incentive to acquire the security of British citizenship, despite the onerous paperwork and prohibitive (and rapidly escalating) costs involved.3 Consistent with this theory, rates of citizenship acquisition by EU migrants have risen sharply since Brexit, as the graph below illustrates.4

Yet the logic of refusing the franchise to settled migrants from the point of view of governments is less clear. The wave of migration from new EU members in the mid 2000s created a large new population that was, and remains, almost entirely disenfranchised. There has been virtually no discussion about whether this is desirable, whether to change anything to address this, and if so, how. The issue is simply not talked about. One consequence has been to skew the migration debate — millions of settled migrants, in particular EU migrants, have no votes, but those who dislike their presence do have votes, and have used these effectively to mobilise opposition to immigration in the EU referendum and in the general elections since. The guarantees offered by EU citizenship have, partly as a result, not turned out to be as secure as once expected.

Yet even after Brexit, the idea of extending the franchise to the millions strong community of disenfranchised long term resident migrants, including the many EU citizens whose fundamental rights have now been curtailed, continues to attract little attention. This seems both politically unwise and inconsistent with democratic norms. Giving EU citizens easier access to the ballot would be a valuable way to demonstrate goodwill to this large and important settled community, who politicians regularly claim they value and wish to support, and who have close links to the European partners with whom the new Labour government says it wants a “reset”.

Actions speak louder than words — and the ballot is a powerful way to hold politicians to their promises. A generous reform of political rights to enfranchise settled EU migrants would be a powerful demonstration of goodwill to the EU itself: what better way to demonstrate that settled EU migrants are valued than by granting them the same voice in the political system Commonwealth migrants already enjoy? Maintaining strong relations between Britain and the Commonwealth was the reason political rights were extended on generous to Commonwealth migrants decades ago. The same logic applies to settled EU migrants today. It would be good politics, too: EU citizens newly armed with the ballot would be more favourably inclined to the party which helped them gain a political voice.

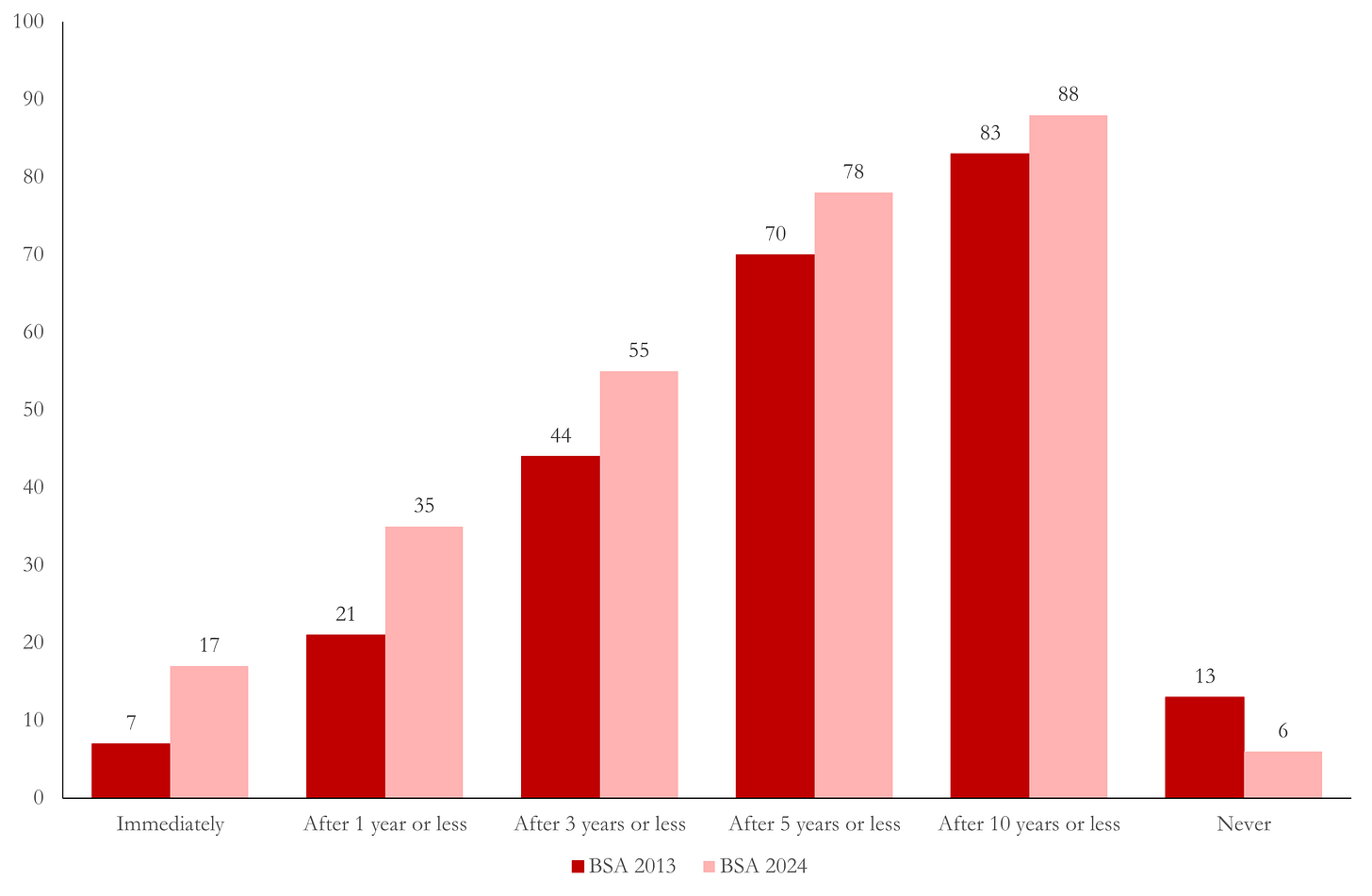

Two obvious objections arise. Firstly, that the native British population would oppose extending the franchise in this way. This view seems to be widely held in political circles, but it is not backed up by the data on public opinion. Polling by the British Social Attitudes (BSA) from 2013 showed more than seventy per cent of respondents supported extending the franchise to settled migrants after five years or less. Politicians might assume that the past decade of polarised argument over high migration will have produced a more sceptical public, less willing to extend political rights to the now much larger settled migrant population. In fact, the opposite has happened - support for franchise extension at any given qualification period is higher now than a decade ago. For example, the share of respondents supporting an extension of the franchise after 5 years rose from seven out of ten to nearly eight out of ten. Support for the current policy of permanent disenfranchisement fell over the decade from 13 per cent to 6 per cent.

In short, more than eight out of ten voters would support granting full political rights to migrants after a five year qualification, while only about one voter in twenty supports the status quo policy of never granting full political rights to settled migrants who don’t have them already. The consensus in favour on enfranchising migrants has become stronger over a decade of high migration and polarised debates about migration levels.5 Such polling suggests that, far from being a “brave”, risky or contentious change, granting the franchise to all settled migrants who have lived here continuously for a long qualification period is seen by the vast majority of voters, of all political persuasions, as basic common sense.6

Cumulative support for extending the franchise to settled migrants working and paying taxes in Britain after different qualification periods, 2013 and 2024

Source: British Social Attitudes 2013 and 2024. Precise question wording: “When should migrants who are working and paying taxes in the UK be able to gain the same rights to political participation as UK citizens?”

A second objection is that the right to vote in general elections is inextricably bound up with national citizenship. Extending it to non-citizens would, on this view, harmfully dilute the meaning of citizenship itself. There are two responses to this. Firstly, Britain severed the link between citizenship and voting right generations ago. As already discussed, citizens of Commonwealth countries and Ireland have the right to vote in general elections from the moment they arrive in Britain. This right has existed for many decades and has not proved controversial. Secondly, the reform need not take the form of granting the vote to non-citizens. Instead, access to citizenship itself could be made easier. For example, the millions of long term resident migrants who have already been granted settled status by the British government could be offered a lower cost, faster track to British citizenship. This would overnight enable millions to more easily join the political process — but without obliging any to do so.

Offering the millions of settled migrants who have made their lives here an easier route to secure the most basic of political rights — the right to vote in a general election — would be a powerful way for the British government to demonstrate to people who have made their home in Britain that they are welcome here in the long run. It is respects a basic democratic principle with near-universal public support: that all those with a stake in political decisions, regardless of where they originally came from, should have a voice in those decisions. It is time for British politicians to respect an ancient Polish principle — “Nic o nas bez nas”: “Nothing about us, without us”.

PS - Following helpful suggestions on social media, two changes have been made to the original version of the article. The title of the final graph is now more closely tied to the wording of the question used, with the full wording provided below the graph. And I have provided a footnote explaining the discussion focuses on the Westminster franchise, as many non-Commonwealth migrants can already vote in local and devolved elections (their ability to do so has not proved at all contentious, which further supports my contention that there is broad support for giving settled migrants an equal say in the electoral process ).

Resident EU citizens can vote in local elections, and all resident migrants can vote in devolved Scottish and Welsh elections (neither has ever proved contentious, again illustrating that political rights for settled migrants are broadly accepted). However, neither EU citizens nor non-Commonwealth migrants can ever vote in Westminster elections where any of the most important aspects of national policy are decided.

I should declare an interest: My mum was one such EU citizen. She arrived in 1976, and despite a keen interest in politics was unable to make her voice heard in any general election from then until her death in 2022, as - like the majority of her 86,000 fellow Dutch nationals - she opted not to take British citizenship.

A recent report by the Oxford Migration Observatory notes that the fees involved in acquiring British citizenship are “among the highest in the developed world”. Naturalisation fees alone would now set back a family of four (two adults, two children) £5,588. There are also many other fees and legal costs involved in the process.

As settled EU migrants regularly cite high fees as one major reason they do not acquire British citizenship, reducing such fees (and the associated paperwork) would provide another route to improving the political integration of these communities

For example, a large majority of those with the most negative views of the economic impact of migration nonetheless support enfranchising migrants - 55% of such intensely sceptical voters would back enfranchisement after 5 years, and 78% after 10 years. The equivalent figures for voters neutral about the economic impact of migration are 80% and 88%, while for voters positive about the economic impact of migration the figures are 89% and 92%. For more detail, see the full BSA 2024 report on immigration available here: https://natcen.ac.uk/publications/bsa-41-immigration

Support for extending voting rights to 16 and 17 year olds, a Labour manifesto commitment in 2024 is by contrast much lower, with opponents outnumbering supporters in most polls

The increase in the cost of citizenship really rankles. I received my British citizenship around 2002-3 and it cost around £70, similar to the cost of a civil wedding at the time. The cost shot up and it seemed like a way to make money out of people who couldn’t vote against it. Piddling sums of money to the government but huge to families and couples at what should be a happy time.

I was shocked recently to find out how much it costs to apply for citizenship. When someone has been here for most of her life, over 25 years, has a son going to school here, has been paying taxes here and contributing in other ways, yet they still want £1630 out of her.