Today is, by my reckoning, the 21st day of this campaign, with 21 more days to go. It’s half time. A good point to grab a cup of tea and look at the lay of the land. This campaign started with an unforced error, as a Prime Minister without an umbrella was drenched in a downpour while telling voters he was the man with a plan. It has since been defined by another, as in the midst of a campaign focussed on winning back socially conservative pensioners, Rishi Sunak departed D-Day commemorations in Normandy early and then pre-recorded a TV interview.1

The media chattering class (including many who are traditionally allies of the government) have not been impressed by the Conservative campaign to date. But what about the voters? Have they now written off a trailing Conservative party, or are there still signs of life? Here’s a quick look at some of the main polling indicators, as we hit the halfway point. Where possible I aggregate information from multiple pollsters into an average, but also provide some discussion of any disagreements between pollsters and/or distinctive results.

Perceptions of the campaigns: a bad start for the Tories, a good start for everyone else

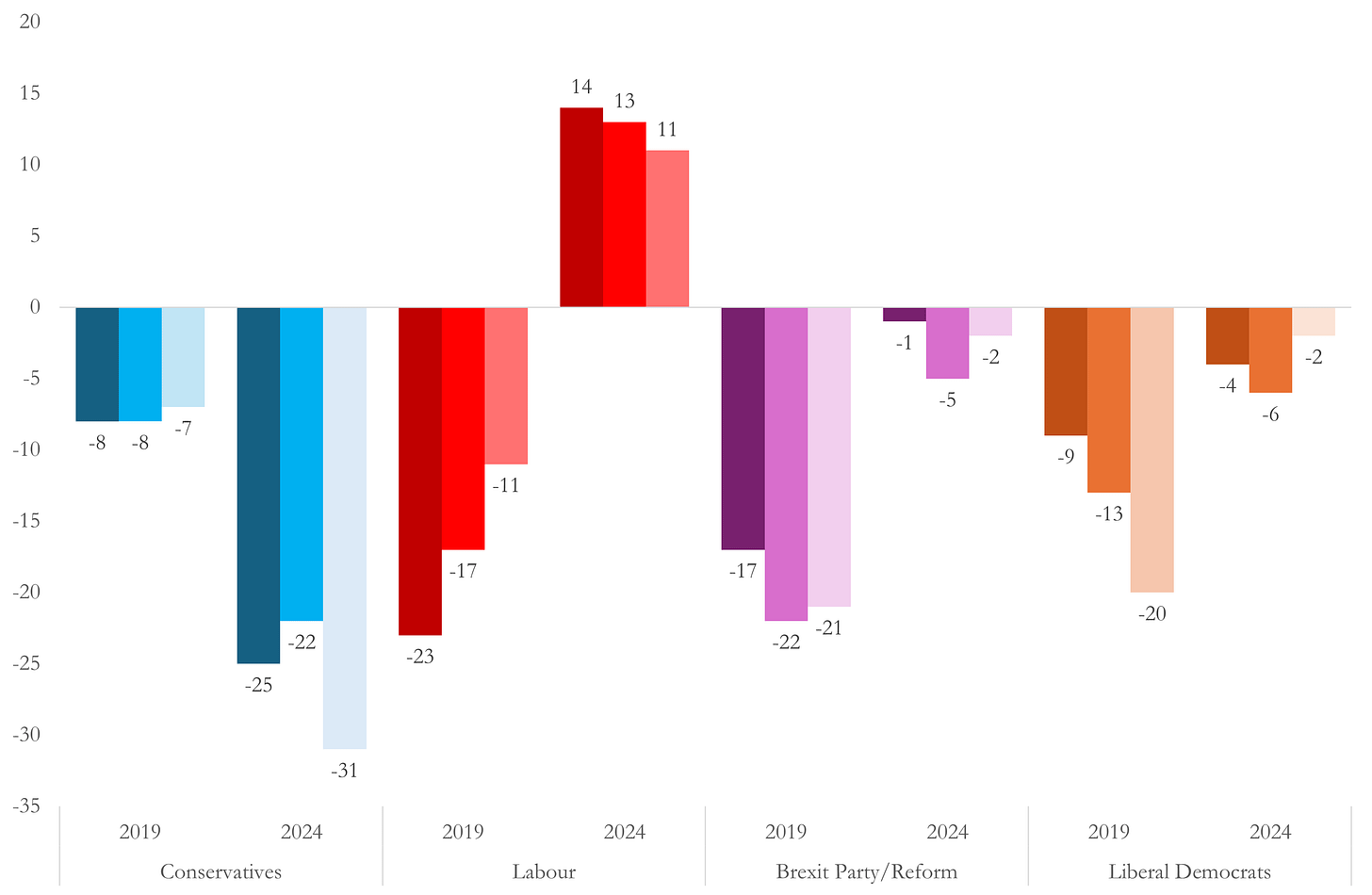

We can start with the simplest measure of campaign success or failure - the direct verdict of voters on what they have seen and heard. IPSOS-MORI ask voters each week whether they think each party is having a good or bad campaign (regardless of who they personally support). IPSOS-MORI asked the same question in the same way during the 2019 campaign so we can compare the parties’ performances now with then. The picture, set out in the chart below, is very clear: the Conservatives are doing much worse than in 2019, and all three of their opponent parties are doing better, with Labour registering the largest improvement.

The Conservatives’ ratings in 2019 were in fact rather mediocre - mildly negative in the first three weeks - but their ratings this year are awful, and consistently worse than last time. The Tory rating of -31 in week 3 of this campaign is the lowest net score by any party in either year - and with the D-day blunder still to fully register in polling there may be worse to come. Labour’s net ratings this time started very positive - the +14 rating is the best score by any party in either year - but have faded a little (this contrasts with 2019, when they started with very poor ratings then gradually improved). Both the Liberal Democrats and Reform have been treading water with slightly negative ratings this time (with a lot of don’t knows) but this is a substantial improvement on 2019, when the Brexit Party campaign was judged very negatively from the outset, while under Jo Swinson the Lib Dems’ ratings fell off a cliff in the early exchanges.

Assessments of each party’s campaigns in the first three weeks, 2019 and 2024

Source: IPSOS MORI

The headline numbers - nothing has changed…

While the public clearly judge the Conservative campaign more negatively than everyone elses, that judgement hasn’t fed through into headline voting numbers, perhaps because the Conservatives started so far behind they cannot really fall much further. While the odd poll has grabbed attention with bumps or slumps , the overall pattern from the first half of the campaign is stability, particularly in the battle between the ‘big two - Labour’s lead over the Tories is pretty consistent in the polling averages, and with most of the individual pollsters too, though they vary a little in how they see the race. Labour has posted stable leads of around 20 points throughout the first three weeks, as it has for many months now.

But there is some movement. Both main parties’ have seen a small drop in their average support in the most recent couple of weeks, with some pollsters recording larger drops. On the other side of the coin, Reform UK have risen in the averages following the return of Nigel Farage as party leader last Monday. Pollsters vary on how big this Farage bounce is, with shifts varying from one point to seven points in second week polling.

Week 3 polling, so far incomplete, does not suggest much further advance for ReformUK So far the Farage bounce is the only substantial shift in the polling for smaller parties - the Lib Dems have been fairly constant at around 10 per cent, and the Greens at 5-6 per cent, though the most recent YouGov poll, now employing a new methodology, has suggested a large bounce in Lib Dem support. It remains to be seen if this apparent shift is supported by other pollsters.

There are also, however, large and enduring differences between the pollsters methods and results, which have been added to in recent days as several pollsters including YouGov and MoreInCommon make substantial changes to their methods. Estimates of Labour in week 3 to date range from 38 (YouGov) to 46 (DeltaPoll), while estimates of the Conservatives range from 18 (YouGov) to 26 (Savanta) and for ReformUK estimates range from 17 (YouGov, Redfield and Wilton) to 10 (Savanta). While the average is usually a more reliable guide, it is also quite possible that one or another of the various approaches being taken by pollsters with views a long way from the average proves in the end to better capture the big shifts we are seeing this year. Only time will tell.

Poll averages pre-campaign and across the first three weeks of the campaign

Source: Weekly average of all pollsters’ final pre-campaign polls. Week 3 average is incomplete as not all regular pollsters have yet been published

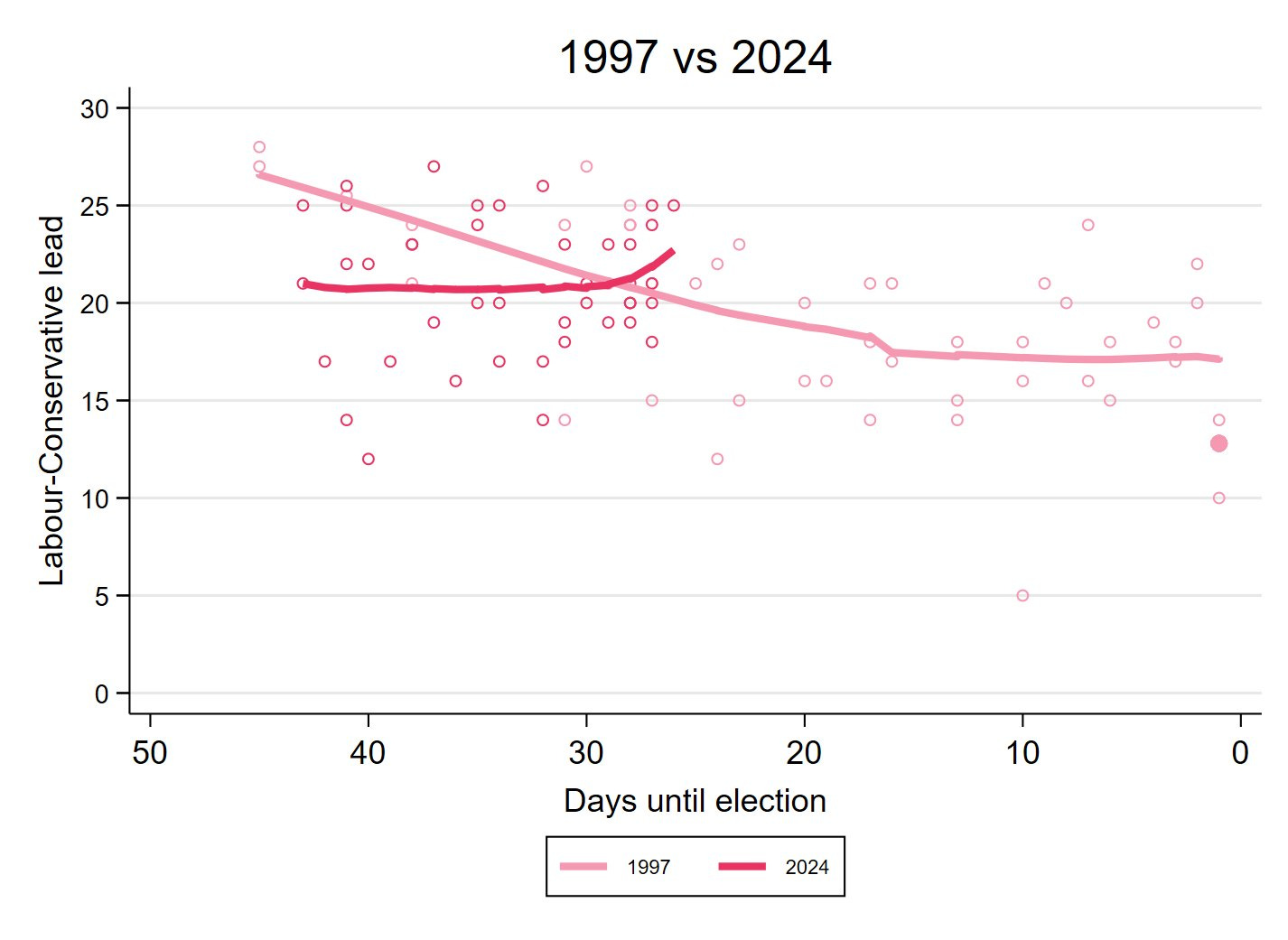

The current stable picture suits Labour just fine, as the long anticipated narrowing in the polls continues to elude us. But a stable campaign piles further pressure on Rishi Sunak and the Conservatives who are now staring down the barrel of a historic defeat. As recent analysis from Will Jennings has recently shown, Sunak’s campaign has now fallen behind that of John Major in 1997. By this point in the 1997 election, Major’s soapbox focussed electioneering had begun to narrow the polls, a narrowing which continued all the way through to polling day and helped mitigate the Conservatives’ last landslide defeat. Nothing similar has happened for Sunak yet, and at this point a sharp narrowing in the polls, or a large polling error, is needed to avert disaster.

Things can only get better? Labour poll leads in 1997 campaign polls and in the first weeks of 2024 campaign

Source: Will Jennings

Leader approvals - Sunak well behind

Conservative and Labour leader approvals in pre-campaign polling (IPSOS MORI)

This is the first general election campaign since 2005 where the Conservative leader began behind their Labour opponent. This poses serious problems for the Tory campaign, which like all its recent predecessors has been framed around building up a strong and decisive leader. The Conservatives badly needed to deliver a boost to Sunak’s leader approvals or their leader-focussed campaign risks reinforcing weakness rather than building strength.

A clumsy and error strewn Sunak campaign has however entirely failed to shift the dial on leadership approval. The various pollsters who monitor leader approval have recorded no change at all in the share approving of his leadership, and a slight increase in the share disapproving. Keir Starmer’s ratings have also been largely stable, though with some evidence his approvals may have risen slightly, and his disapprovals fallen, in the most recent week of the campaign (but we don’t yet have all the readings for this week).

Average Sunak and Starmer approval ratings in the first three weeks of the campaign

Sources: BMG, DeltaPoll, JL Partners, IPSOS-MORI, Opinium, Redfield & Wilton, WeThink

Half way through, Starmer remains far ahead of Sunak, who is as toxic with 2024 voters as Jeremy Corbyn was in 2019. Boris Johnson wasn’t widely loved in 2019 (contra the mythology promoted by his ardent supporters), but he started that campaign with a big lead over a toxic Jeremy Corbyn and held that advantage all the way to polling day, which proved enough for a big win. Starmer looks to be repeating the trick, and will hope for the same outcome - or better.

The policy offers - no game changers

The policy offers so far in the campaign have reflected the differening challenges facing the parties. The Conservatives, trailing badly, need attention grabbing ideas to try and change the conversation. Labour need credible ideas which flesh out their offer and capture the mood for change but without opening up vulnerabilities or taking risks.

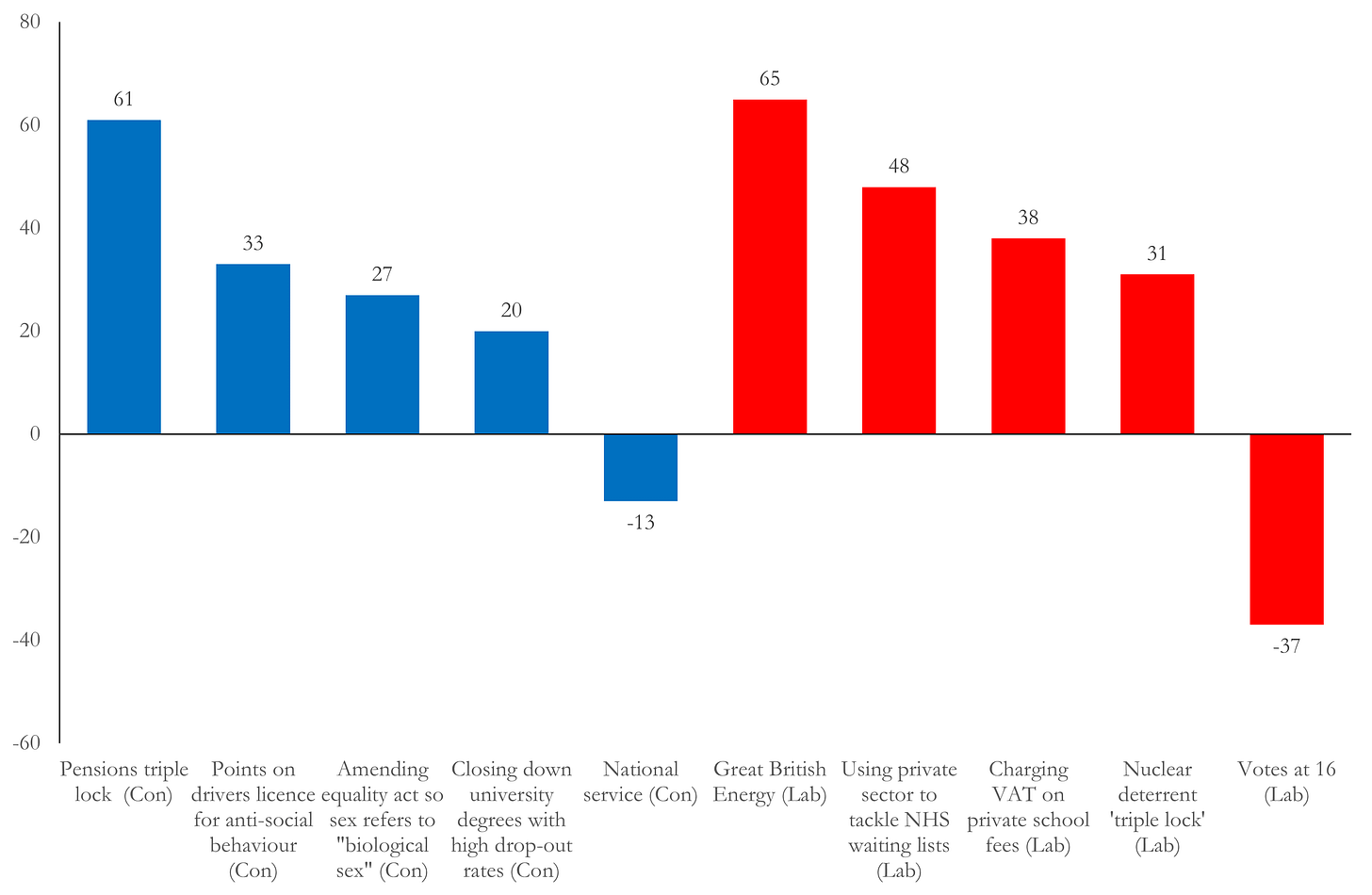

Net support for prominent Conservative and Labour policies announced in the first half of the campaign

Source: YouGov

Both parties have put out a number of popular proposals, as the above chart shows. Labour’s ideas have broader support, but that is by design - the party is putting out uncontentious ideas to address widely acknowledged problems (renewable energy, NHS waiting lists) or bland reassurances (nuclear ‘triple lock’). The proposal to tax private schools is broadly popular, so Conservative attacks on it don’t make a great deal of sense elcetorally. The only disliked idea Labour has put out so far is votes at 16, but this hasn’t had a high profile in the campaign.

Tory proposals, beyond the perennially popular idea of spending more on pensioners, are a bit less popular but they are polarising by design. Proposals to reform the equality act, and clamp down on supposedly dodgy degrees and anti-social behaviour are popular overall and play particularly well with older social conservatives, who were the clear focus of early Conservative campaigning. But most voters didn’t notice these ideas, while the proposal that really did grab the headlines - national service - was both even more polarising and much less popular overall. None of these ideas have as yet moved the dial, though with manifestos only published this week, both parties will hope there is still time to win voters over to their proposals.

Where are Conservative voters going? Are any coming back?

With Conservative support in current polls running at roughly half the level the party achieved in the last general election, the outcome of this election will be greatly shaped by where 2019 Tory voters are going and whether any return to their former party. There are three main flows - Conservative to don’t know, Conservative to Labour, and Conservative to Reform. The story from the first half of the campaign is no news on the first, bad news on the second and worse news on the third.

Share of 2019 Tory voters going to ‘don’t know’, Labour and Conservatives pre-campaign and in first three weeks of the campaign

Darkest shade is pre-campaign, steadily lighter shades are week 1-3 of the campaign.

Much has been made of the large population of 2019 Conservative voters who now say they don’t know what they will do - a source of anxiety for Labour activists worried they haven’t “sealed the deal” with enough of the electorate, and a source of hope for Conservatives who think they can still be won back. The bad news for the Conservatives is such voters are still there, in similar numbers. The good news for the Conservatives is such voters are still there, in similar numbers. While the Tory campaign has not made net gains amongst this group, nor has anyone else. And it is typically easier to win over undecided voters than those who have settled on another party. So scope for some Tory recovery still exists here.

That is the end of the good news for Team Sunak. They have made no progress at all in reducing the share of voters switching directly from Conservative to Labour - voters who count double in the many Tory-Labour battleground seats - one vote off the incumbent’s pile, one vote added on to their main opponent’s. Averaging across the pollsters, fifteen per cent of 2019 Tory voters - more than one in seven! - say they will now vote Labour. That on is sufficient on its own to produce a swing bigger than in 1997, and this number shows no sign of falling. If anything, it is slightly larger in the latest data.

That may seem like bad news enough, but the figures for Tory to Reform UK switching are a nightmare for Tory strategists. Their whole game plan for the early running was to squeeze this group but instead they have lost more ground to a resurgent, Farage fuelled revolt on the right. The share of Tory 2019 voters backing Reform has bounced up from 15% in the first week of polling to over 20% in the second and third weeks post Farage announcement, and may still rise further.

But wait, it gets worse. The publication of nominations confirmed that Reform UK candidates will indeed be on the ballot in the vast majority of seats. Reform are now standing in nearly all of the Conservative seats where Farage stood aside the Brexit party in 2019. However well they do overall, Reform are therefore absolutely certain to hurt Conservative prospects up and down the country, by splitting off voters who could not vote for a Farage candidate in 2019, but can now. Those are voters beleaguered Tory incumbents can ill afford to lose.

The long view: an unprecedented demand for change

The Conservatives’ dismal headline polling numbers, and loss of votes in multiple directions, reflect a broader shift in the public mood, with a historically unprecedented level of discontent with the government and intense desire for change. As one of the longest established pollsters on the British scene, IPSOS-MORI have various indicators that can give us the long view. All of them point to an electoral earthquake.

Rishi Sunak’s net satisfaction rating of -53 is the worst recorded by MORI one month out from an election in all of the elections they have covered since 1979 - worse than Gordon Brown in 2010 (-36), John Major in 1997 (-46) or James Callaghan in 1979 (-33). The net rating of the Sunak government is, at -71, the worst approval of any British government MORI have asked about on the brink of an election (second place goes to the unloved outgoing government of Boris Johnson, who scored -65).

More than two thirds of British voters tell MORI the government doesn’t deserve to be re-elected next month, nearly three quarters say it is time for a change, and four fifths say the government has done a bad job. All of these figures are now at the highest level since Sunak took office. The Prime Minister is urging voters to “stick with a plan that is working”. Record majorities on every measure are telling voters they want to do the opposite. While a miracle of late persuasion cannot be ruled out, at present the most relevant question for Conservative MPs isn’t “can we win?” but rather “can any of us survive?”

The circumstances of this campaign blunder have been hotly contested. Sunak’s critics have claimed this was a campaign decision, cutting short his time at the commemorations to free up time for an ITV interview. Sunak has rejected this claim, saying his itinerary had in fact been set well before the election. In other words, he never planned to stay in France to the end, and then just found a new use for time he was always due to spend back in Britain. It is not clear that Sunak’s explanation really offers much mitigation though, as it implies that it was written into his diary for weeks that the Prime Minister would depart a hugely resonant ceremony early even as multiple other heads of state, and his own ailing monarch, stayed on until the end. If Sunak’s critics are right, the Prime Minister made an obvious blunder on the spur of the moment. If Sunak is right, an obvious blunder was written into the diary for weeks and no one spotted it. It is not obvious how this is a better outcome.

As always a very interesting read, Rob.

Can I ask: once postal voting starts, do opinion polls trend towards the final day exit poll? Or do pollsters exclude people who have already voted?