The Rochdale by-election: Galloway does it again

Veteran firebrand completes his hat-trick of upsets over Labour in a contest defined by controversy

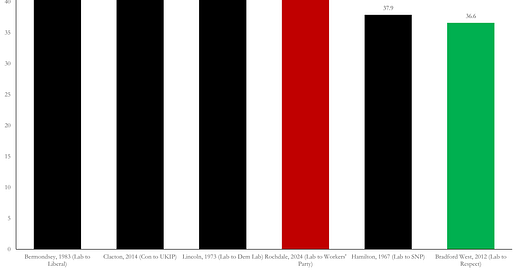

By-elections are seldom boring these days. So far this Parliament we have seen the largest ever swing to a governing party (Hartlepool, 2021); the second largest ever Conservative to Labour swing (Wellingborough, 2024); and the second and third largest ever Conservative to Liberal Democrat swings (North Shropshire, 2021; Tiverton and Honiton 2022). Now we can add the third largest swing against Labour, and the fourth largest swing against any party anywhere – Rochdale’s contributions to the record books. And two of the largest six by-election swings on record share a common characteristic - both have come in contests where George Galloway has beaten his former party.

Largest ever by-election swings

Galloway, the victorious Worker’s Party candidate this week, was expelled from the Labour party in 2003 following interviews in which he seemed to support the Iraqi dictatorship of Saddam Hussein. He has been a thorn in the side of his former party ever since. His first upset victory in 2005, when he mobilised discontent over Labour foreign policy and local conditions to win Bethnal Green and Bow in one of the biggest surprises of the general election night. He repeated the trick in 2012, when he mobilised alienation and discontent among Bradford’s Muslim electorate to secure a massive win in the Bradford West by-election of 2012.1 And this week he got the band back together once again, running an emotive and polarising campaign focussed on local Labour failings and anger at the Israeli invasion of Gaza to defeat Labour in Rochdale. Three Labour seats with large Muslim communities. Three emotive, identity based campaigns fusing international conflicts and local controversies. Three wins for Galloway, campaigning as the outsider standing up to a corrupt political elite.

Here are the scores on the doors from Thursday:

There was much of interest in the result besides Galloway’s striking surge. An independent local businessman, David Tulley, secured more than a fifth of the vote and second place, making this the first by-election of the post-war era where both Labour and the Conservatives had candidates on the ballot, but neither party finished in the top two. ReformUK, who stood the the disgraced former Rochdale Labour MP Simon Danczuk as their candidate, did poorly, winning just six per cent of the vote, less than they managed in 2019. Even allowing for the possible negative effects of a locally unpopular candidate, this was a very weak showing given the party’s current double digit poll shares, and will raise further doubts about their recent polling surge. The Liberal Democrats, once an electoral force in Rochdale, were unable to make headway despite scandals hobbling several of their opponents, winning just seven per cent of the vote. Turnout in the by-election was also fairly healthy at nearly forty per cent, despite the absence of any campaign from Labour in the final two weeks. Galloway’s win was not the result of more voters than usual sitting the contest out.

This was George Galloway’s biggest ever win in terms of swing, but he received a major boost from the unique circumstances of the contest. Labour’s chosen candidate Azhar Ali was embroiled in a major scandal when recordings emerged in which he expressed and endorsed antisemitic conspiracy theories. Labour withdrew their support but it was too late to replace Ali on the ballot paper, so voters in polling stations still found him listed as the official Labour candidate. There is little precedent for a by-election where the incumbent party has disavowed their notional candidate, and has not campaigned at all in the final weeks of the contest.

Rochdale was thus almost like a natural experiment to see how low the Labour vote would go if voters are given no information, are not mobilised, and are discouraged from voting for the party’s notional candidate. It is difficult to imagine more favourable circumstances for outsiders and insurgents. Both George Galloway and the local businessman David Tully rushed to fill the political vacuum left by Labour’s retreat. While Galloway’s success is impressive on paper, the circumstances are a one-off. There are strong reasons to doubt he will hold Rochdale at general election time, and the unique circumstances of the Rochdale contest cast doubt on his claims to be sparking off a more general uprising against Labour.

The doubts begin with Galloway’s own track record. He is much better at winning seats than holding them. After his first upset win in Bethnal Green and Bow, Galloway decided that his constituents in one of Britain’s most deprived seats were best served by their MP appearing dressed up as a cat on celebrity big brother. He was suspended from Parliament, his Respect party split, and he opted not to defend the seat in the 2010 election. His successor as candidate for Bethnal Green and Bow, Abjol Miah, came third, comfortably beaten by the current Labour MP Rushanara Ali.

George Galloway representing his London constituents in 2006

After dubbing his 2012 win in the Bradford West by-election “the most sensational result in British by-election history”, Galloway called it a “Bradford Spring…an uprising…demonstrating a total rejection of the three major parties”. Galloway’s Respect party won five seats on Bradford council in elections held a month later. All five councillors quit Galloway’s party within a year, Respect won no councillors at all in the 2014 Bradford local elections, and the mastermind of the Bradford swing went down to a crushing 30 percentage point defeat to the current Labour MP Naz Shah in the 2015 General election, following an ugly campaign. Within three years Bradford’s supposed “total rejection of the major parties” had turned into a total rejection of George Galloway.

Bradford West election results 2012 and 2015

Galloway’s track record alone suggests Labour need not worry about him as a significant or persistent threat to Labour. He is very effective in acting as a lightning rod for discontent, much less effective at building stable organisations, representing constituents, or building lasting electoral coalitions. Yet many Labour MPs will be nervous nonetheless that Galloway’s continuing appeal signals a broader problem for their party in Muslim communities. Mass protests over the Israel-Gaza conflict have been happening almost weekly for many months, and a recent poll of Muslim voters showed a sharp drop in support for Labour, even without a firebrand like Galloway to mobilise discontent. Galloway may have fizzled out before, unable to cash the cheques written by his own perpetual hype machine, but that is no guarantee that he will fizzle out again.

Yet there remain strong reasons to be sceptical of a broader collapse in Muslim support for Labour, and Galloway’s shock win doesn’t really change these. While there are strong feelings over Gaza in Muslim communities, both of the reliable polls of Muslim voters taken since the current Gaza conflict began show the Middle East taking a distant second place to domestic concerns over the economy, the cost of living and the NHS. Voters know, when casting ballots in a by-election held mere months before a general election, that the contest can be treated as a ‘free hit’, an opportunity to voice their anger on specific issues safe in the knowledge it has no impact on who will form the government. Labour’s withdrawal from the election will only have increased the sense that it was a protest vote opportunity. Voters know the stakes are much higher in a general election, and change their behaviour accordingly. By election upsets are often overturned at the next general election - as Galloway himself is well aware.

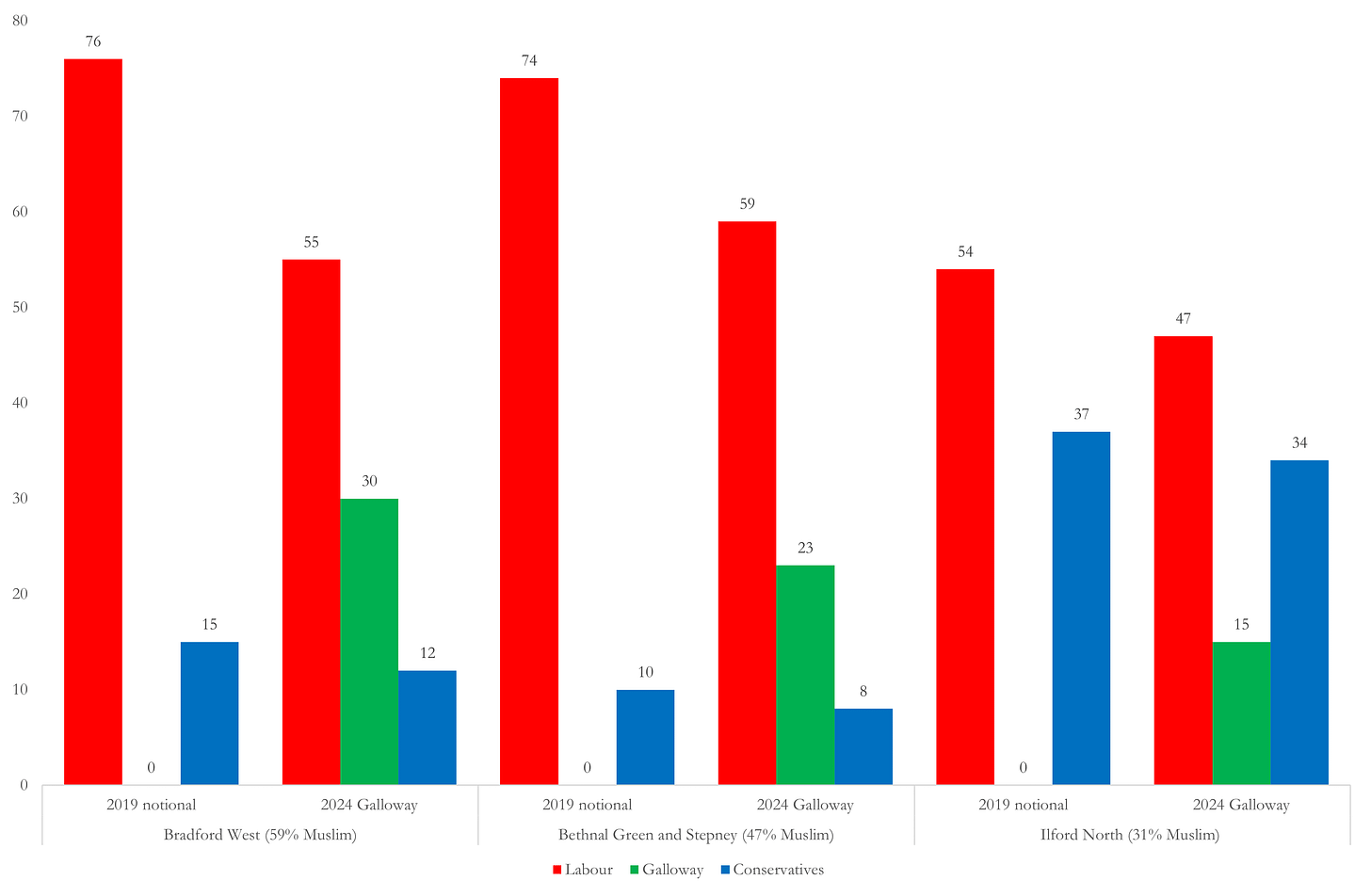

But “often” is not “always”. There is a different way of viewing Rochdale, as part of a growing body of evidence of a real electoral risk in some safe Labour seats. As I argued a few weeks ago, that risk is low even in the swing away from Labour among Muslim voters is huge. That argument still holds up even if we make some very generous assumptions about Galloway’s appeal in a general election. Take, for example, Ilford North; Bethnal Green and Stepney and Bradford West. The first two are seats Galloway named as targets for his “movement” in his victory speech from the Rochdale count, while he has a proven appeal in Bradford West, having won it in 2012. Could a Galloway insurgency pose a real threat to Labour MPs Wes Streeting, Rushanara Ali and Naz Shah?

We can put this idea to the test using a modified version of the projection model I used in my earlier Swingometer analysis of Labour and Muslim voters. Let’s start with the assumption that Galloway or one of his allies wins half of the Muslim vote in each seat - this would be an exceptionally strong performance in a general election.2 Let us be more generous still by assuming no swing to Labour at all among non-Muslims - which would be a massive under-performance relative to current polls. Even in this scenario, which bends over backwards to be generous to Galloway, he does not come close to winning, or to changing the outcome in any of these three seats. Labour are simply too strong, and the Muslim vote is simply not large enough, for Galloway to win, or even to split the Labour vote enough to hand Wes Streeting’s Labour vs Conservative marginal of Ilford North to his Tory opponents. If Galloway cannot win any of these seats even if we assume no swing at all to Labour, his prospects are not great in a general election where a double digit swing to Labour overall is more likely.

A Galloway surge scenario - projected results in three Labour seats if a Galloway candidate won half of the Muslim vote and there was no swing to Labour among non-Muslims

2019 notional results from Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher

Even in the worst case scenarios, it is therefore hard to see Galloway causing Labour many problems. His appeal would need to broaden dramatically, or Labour’s national position weaken dramatically, to pose a real threat. And even then, the number of seats affected by a Galloway uprising would be too small to materially impact the overall election outcome. Yet, despite all of this, Galloway’s victory this week will reverberate through the Labour party. Perceptions matter. Even though the risk Galloway poses is small, it is both real and hard to quantify, and in volatile and uncertain times, politicians will understandably be wary. MPs representing seats with large Muslim communities will worry that advances by Galloway and his allies pose a credible threat, if not in this election, then in contests to come. They will push for support from the national Labour party to manage that risk.

Many within Labour will also point to Galloway’s resurgent appeal as further evidence of a more fundamental problem: growing alienation from Labour in Muslim communities which have backed the party for generations. They will argue this problem needs urgent action from the party which has long seen itself as the champion of marginalised minority communities, even if seats are not on the line. All of this will lead for calls for Labour to articulate Muslim concerns more effectively, and devote more resources to organising and campaigning in Muslim areas. And that, in turn, will pose new problems for Labour strategists already stretched thin in an election where Labour will be targeting 150 seat gains or more to secure a comfortable majority.

The Labour leadership would dearly love some hard evidence that the Rochdale result was a one off to reassure worried MPs and activists. The electoral gods have smiled on them in this regard, as two golden opportunities will come within months. A recall petition is currently underway in Blackpool South – it is likely to succeed and trigger a by-election contest in a marginal Conservative seat. A Labour win should not be in doubt, but a really dominant win on a large swing would help calm nerves and show the opposition is still on course despite the Rochdale ructions.

Then in May we have local election contests up and down England, with council seats up for grabs in many Labour local authorities with large Muslim communities including Bradford, Blackburn, Oldham, Manchester and Rochdale itself. Galloway himself has already thrown down the gauntlet for May’s contests, saying at the Rochdale count that he wanted “to put the town councillors on notice that we intend to clean the town hall clock”. Slates of Galloway aligned candidates are now expected to stand this spring, and in all of these authorities and others there will be wards where a large majority of voters are Muslim. If Labour can defeat Galloway allies in such wards, it will be a strong signal of the party’s resilience in such communities despite the challenges of the past six months. If, on the other hand, Galloway can get multiple allied councillors elected, it will be a clear sign that Labour face their most serious challenge among Muslim voters since the years after the Iraq war.

Number of 20 point plus swings in a Parliament

This week’s earthquake was yet another reminder that we live in volatile political times. This Parliament is not yet done, but it has already seen substantially more twenty point plus by-election swings than any previous Parliament. Old loyalties are fading fast, and the electorate has never been more mercurial. For now, voters’ anger in the general election to come later this year looks set to be focussed primarily on a failing and unpopular incumbent Conservative government. But such anger can rapidly find new targets. Labour have to worry that their polling strength is driven more by rejection of a failed status quo than endorsement of any specific alternative. If Labour win, they could rapidly shift from being the beneficiaries of voter anger to being its target.

Populists and radicals like Galloway do not have to operate under the constraints of government. They can rail against failure without putting any credible alternative on the table. As we saw in Rochdale this week, the appeal of such a purely negative populism is enduring in communities who feel government has failed them. Rochdale is a warning for a Labour party currently dreaming of a return to government. The hopes of change the opposition are mobilising will be hard indeed to deliver upon when governing in straitened times. And when hopes are disappointed, challengers will be waiting to pounce.

The story of Galloway’s Bradford win is a complex one, and is well told in an excellent report written by Lewis Baston, “The Bradford Earthquake”, which can be read here: https://democraticaudituk.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/bradford-earthquake-full-report-web.pdf

In calculating the impact on Labour and the Conservatives I assume, in line with the most recent Survation poll, that 85% of Muslim voters voted Labour in 2019 and 10% vote Conservative. The results, however, don’t really hinge on the precise figures used here.

Slightly nerdy comment, but contra this article this was not the first postwar by-election where neither Labour nor the Conservatives finished in the top two. That distinction goes to Eastleigh 2013, where the Lib Dems held the seat and UKIP were the runners-up.

GG...what does he do as constituency MP? Does he perform role of redress for constituents and hold gvt to account?