Predictions are a hazardous business in politics, but they are worth making every so often anyway. Being wrong in public is a good check on the ego and encourages reflection on what was missed or misunderstood at the time the prediction was made. I picked up this habit of annual predictions audits from two politics analysts - Stephen Bush and Sam Freedman - whose work I admire. My own spin on this is to get people to ask me for predictions of the year ahead at Christmas time, make those predictions on the spot without faffing around, then review them at the end of the year. Its time to mark 2024’s assignments.1 I’ll be putting out the call for new prediction questions on Twitter and Bluesky in coming days - I will add the links to the predictions threads here or you can ask me for a prediction in the comments section below.

My predictions from last year can be split into three groups: predictions about the British general election, which I grouped together in one long post; miscellaneous British politics predictions; and predictions about politics around the world. I’ll take these in order, starting with my general election prediction scenario, which ended up fairly close to the mark - but consistently missed in an interesting way; then assorted predictions about British politics in 2024 outside of the general election; and finally a miscellany of hit and miss global politics predictions.

General election predictions

The biggest focus of last year’s predictions was unsurprisingly the general election widely expected for 2024. I decided to link together all of my predictions in a fully worked out scenario for the general election, attempting to think through numerically how each party would do, and what the knock on effects on others would be, starting with the smaller parties and working upwards from there. This was laid out in a long post at the start of the year - you can read it in full here. Here are the individual predictions and how I did on each:

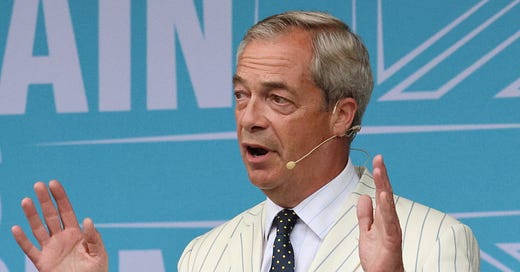

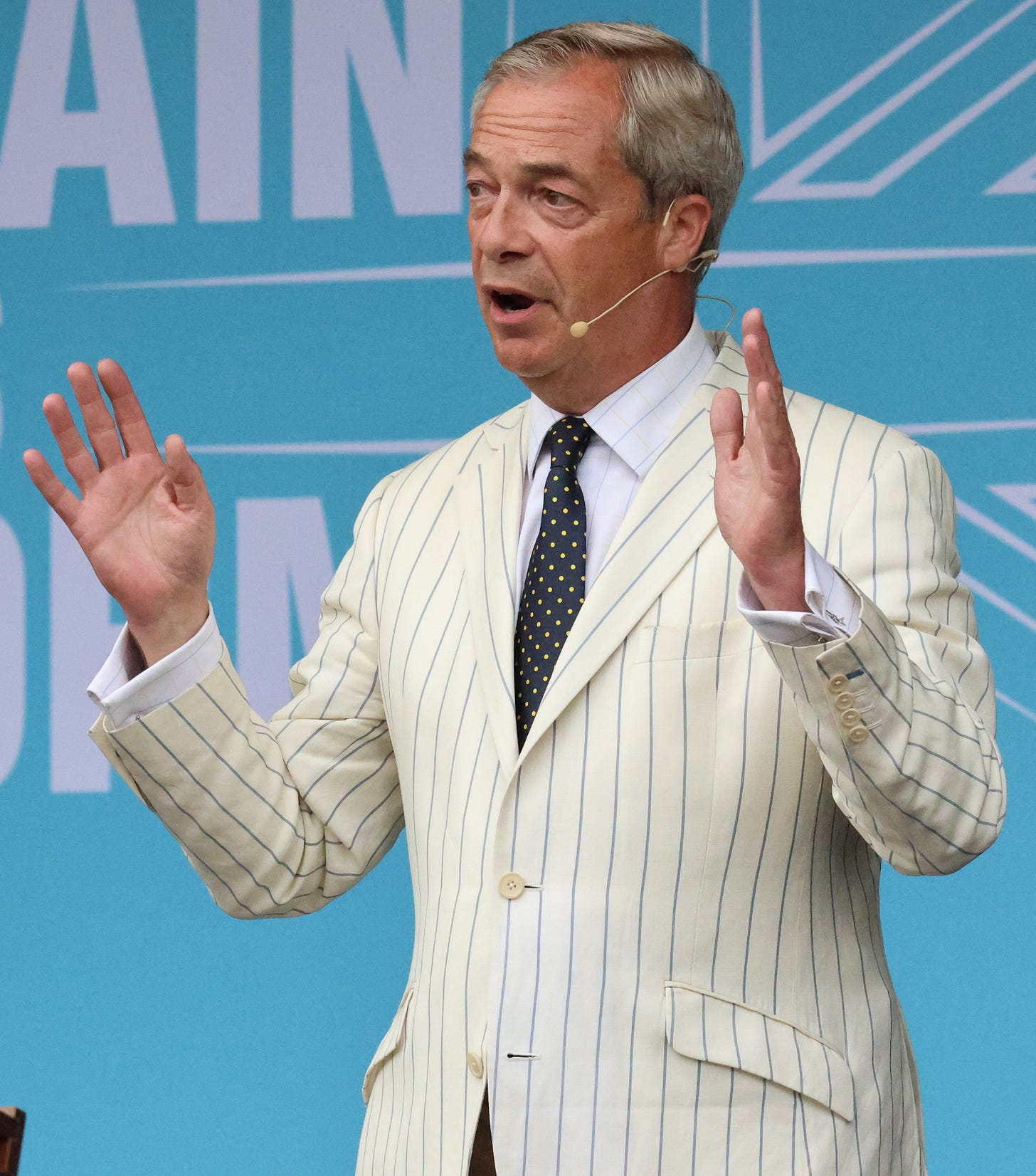

Nigel Farage will return - he did.

Reform will, partly as a result poll well (10% in England and Wales) - they did - and Reform got a big polling bump from Farage’s return, as predicted. But Farage’s latest party ended up doing much better than I forecast - 15% in England and 17% in Wales (and 7% in Scotland, where I did not expect much success for them).

Most of the Reform vote comes from the Conservatives - it did - the Tories lost far more votes to Reform than to anyone else, and Farage’s ability to split the 2019 Tory coalition cost the Conservatives a lot of seats.

Lib Dems get a similar vote share to last time, but much more efficiently distributed thanks to tactical voting - they did and it was, resulting in the highest Lib Dem seat total since 1923.

Greens poll well (4.5% overall) but their support is concentrated in safe Labour seats - the Greens did poll well, and their support was concentrated in safe Labour seats, but they did even better than I thought - winning over 7% of the vote in England and over 10% in London (with the strongest performances in London and elsewhere nearly all in safe Labour seats)

Scottish Labour overtake the SNP, and outperform uniform swing, with bigger SNP to Labour swings in traditionally Labour central belt seats - all of this came to pass, but Scottish Labour did even better (taking 37 seats), and the SNP even worse (losin 39 seats), than I expected. The Scottish Liberal Democrats also did better than I expected, taking 6 seats.

Combined share for the “big two” (Labour and Conservatives) falls sharply to 68.5% - the big two combined share did fall, but much more sharply than I thought, to just 59% of the GB vote - the lowest level ever in the 102 years since Labour first broke into the top two in 1922.

Conservatives recover some ground relative to end of 2023 polls and finish on 28% - while the Tories did end up outperforming the polls, they didn’t recover ground in the campaign (instead falling further) and ended up on 24.4% of the GB vote and 121 seats - their worst ever performance in both votes and seats.

Labour lose some ground relative to end of 2023 polls and finish on 40.5% - Labour did lose some ground in the short campaign, but fell much further than I expected (in part due to a large polling miss against them, which I did not forecast), ending up with 34.6% of the GB vote, 6 points below my prediction.

Intensive tactical voting boosts performance of both Labour and the Liberal Democrats where they are the local opposition to the Conservatives - This came to pass much as predicted. Indeed, the degree of tactical co-ordination was truly extraordinary, and related unionist tactical voting looks also to have helped Scottish Labour and the Scottish Lib Dems gain extra seats, and helped the Greens take two Conservative seats.

Conservatives to under-perform uniform swing in Leave voting seats without a 2019 Brexit Party candidate due to Reform UK joining the ballot - this came about, and how. The scale of the Conservative drop mapped strongly onto the estimated vote for Brexit in 2016, which meant some truly colossal drops in Tory support in very Leave voting seats where Farage didn’t stand a candidate in 2019.

Resulting seat prediction: Labour 388, Conservatives 156, Lib Dems 64, SNP 18 - Errors on the four predictions: Labour -23 Conservatives +35 Lib Dems -8 SNP +9

Guess who’s back? Back again?

Nearly all of these predictions got the direction of travel right, but in a number of cases I identified the trend correctly, but underestimated its strength. Its worth pondering both aspects. The broad brush strokes of the 2024 general election were already on the canvas when I wrote these predictions January 1st- the Conservatives were on course for a heavy defeat, Labour for a big win, and a recovery in Scotland, and the smaller parties were on course to do well once again as the binary grip of Brexit finally eased. Nothing between January 1st and July 4th changed any this picture. Arguably the two big parties’ fates had been set since at least the Liz Truss firework display blew up any Tory hopes of recovery, while the return of fragmented voting became the likeliest outcome as soon as the Brexit deals were inked, removing the strong centripetal force of a binary referendum argument, which temporarily reversed a long running trend towards more plural politics.

I didn’t predict Liz Truss losing her seat to Labour on a record breaking swing, but that happened, and in retrospect it seemed somehow an inevitable conclusion to her Parliamentary career.

None of it was quite so obvious at the time. In particular, the sheer scale of the waves about to break were underestimated across the board, despite plenty of evidence something massive was building just over the horizon. The Tories were widely expected to recover some ground, and Labour to falter somewhat, despite little in the polling at the time to support either conclusion. No one was really discussing Scotland much, even though the turmoil in the SNP, unexpected in 2023, was very much an established part of the landscape by the start of 2024. Many - either from hope or fear - were predicting Farage would do another deal with the Tories ahead of the general election, ignoring both the vast differences between the context of the 2019 “Get Brexit Done” election and the 2024 “Get the Tories Out” election, and the longstanding anti-Tory trajectory of Farage’s political career since the mid-1990s. No one quite took the idea of a Lib Dem wave seriously despite two years of massive gains in local elections and massive swings in by-elections (indeed, the Lib Dems on 60 plus seats was the aspect of my prediction which got the most push-back in early January). And few expected any real earthquakes on the left, despite big Green gains in local elections for several years in a row, giving them a far larger local government cohort, and several months of very visible anger and protest over Gaza, concentrated in British Muslim communities.

The iterative, history numbers based approach I used helped me tie myself to the mast a bit and resist the siren call of the vibes. History suggested lower turnout and higher fragmentation, so that’s what I predicted, and that’s what happened. On Farage and Reform, I could claim a little bit of expert knowledge having studied UKIP and the radical right for over a decade, but it didn’t take an expert to see that a context featuring widespread voter anger at a Tory government deemed to have failed on immigration and Brexit was one he would find impossible to resist. Anyone who thought Farage would seek to bail a struggling Tory government out rather than try to drown it simply hadn’t been paying attention to what the man had been saying and doing for decades. The prediction of a big tactical voting boost for both Labour and the Lib Dems was also firmly grounded in polling and local elections data. I think the outcome vindicates my approach and indeed will encourage me to stick to what my read of the data suggests, regardless of whether it fits the conventional wisdom.

But I still underestimated the scale of change across the board. The problem, I think, is the collision of two principles: the psychology of mean reversion and the reality of ever rising political volatility. Mean reversion is a pretty useful rule of thumb most of the time - the best prediction for tomorrow is what happened yesterday, unusual shifts tend to dissipate, stability is the norm. I think this is a lens we often unthinkingly apply to politics - not without reason, as stability *was* the norm for long periods in the past, so it an expectation with some grounding in history. But also, in a highly uncertain and volatile environment, we tend to just feel that the more familiar outcomes are more likely, whatever the evidence may say. Brexit can’t happen. Scottish Labour can’t lose. The Red Wall can’t fall. The Lib Dems can’t “win here.” The Greens can’t take multiple seats. Independents can’t take multiple seats. The Tories will recover, somehow, because winning elections is what Tories do.

But in volatile times “tomorrow will be like yesterday” is a worse than useless rule of thumb. It leads us to overlook dramatic changes happening right under our noses, and dismiss the evidence of our eyes and ears. Voters have never been less happy with politics, less attached to the traditional parties, or more open to new approaches. Change should be the rule in such circumstances, not the exception. And it has been for a while now. In such a volatile climate, it is prediction of stability that should be regarded with higher suspicion, and need bolstering with strong evidence. Change is the norm, and more change is what we should expect when looking forwards. The polls have already registered big shifts in party support and government popularity in just a few short months since the general election. The political rollercoaster isn’t done yet. Perhaps we need some new rules of thumb to avoid being seduced by the status quo and surprised yet again by volatility:

Don’t expect stability if the numbers point to change.

Don’t back insiders if the numbers show insurgents gaining.

Past performance means less when voter loyalties are weak and voter trust is low.

Tomorrow doesn’t have to be like yesterday, and often won’t be.

Assorted non-general election results British politics predictions

Away from the general election, there were lots of questions about political personnel changes in 2024. On the Tory side, I was asked whether Sunak would bring back Theresa May, whether Andy Street and Ben Houchen would survive as metro mayors, whether a local election rout would lead to a move against Sunak, and who would be Tory leader come the end of the year.

I correctly predicted May wouldn’t be back - there was no obvious vacancy for her nor was there any obvious political rationale for her to return. I correctly predicted the anti-incumbent tide would be too strong for Street to survive despite his strong personal brand (though I wouldn’t have predicted how tight the outcome was), but I wrongly predicted the anti-Tory tide would sweep away Ben Houchen as well. Though he suffered a huge swing against him, slashing his local majority, he nonetheless scraped through for a third term as mayor of Tees Valley. In particular, I over-rated the importance of national media controversies about Houchen’s administration, even pondering whether they might lead to him resigning. Houchen shrugged off the scandals, and enough Tees Valley voters did likewise to keep him in office.

I correctly predicted that there was no Tory result in May that would be dire enough to lead to a move against Sunak, because no one would want the job with so little time left to turn things around. This proved accurate - the Tories endured a shellacking but there was no move against Sunak.

I did, however, erroneously predict (with high confidence!) that Sunak would still be with us as Tory leader at year’s end. This was a knock on effect of getting the election date wrong - as I expected a late autumn poll, I didn’t think there would be time to replace Sunak before 2025. Wrong on both counts. I was right, though, to predict that there would be lots of contenders and whittling the contest down to a final two candidates to take to members would take a while - six candidates stood (nearly 5% of eligible MPs!) and it took over two months to get down to the final two.

Finally on the Tory front I was asked if the Conservatives would split. I said no, with 90% confidence, because a split made no sense before the election, harming everyone’s prospects, and there was in any event already a viable right wing insurgent party for the disaffected to join - ReformUK. Both arguments held up well.

There were questions too about Labour choices. I was asked whether Starmer would do a post general election reshuffle; who would be the incoming Labour PM’s first Home Secretary; and whether celebrity Labour fans Eddie Izzard and Paul Mason would get selected as Labour candidates.

I said I was 80% certain Starmer wouldn’t do a big reshuffle on coming into government, as it would both distract and weaken the incoming administration, with the 20% uncertainty reflecting the possibility of resignations. This held up well - nearly all the senior figures in Starmer’s Shadow Cabinet are now doing the same jobs in government, and most of the changes in personnel have come through lost seats (which I didn’t anticipate) and resignations (which I did).2 I rated Yvette Cooper as 90% certain to still be in post as Home Secretary come the end of 2024, and there she still is, despite a rocky few months in one of any government’s toughest roles.

I said I was 80% certain neither Mason or Izzard would get selected, as local Labour parties had shown no enthusiasm for celebrity outsider candidates and had rebuffed them before. So it proved - Labour members had already turned down Izzard for Brighton Pavilion and Sheffield Central, as far as I know, she did not put herself forward as a candidate anywhere else in 2024. Mason put himself forward for Islington North but did not make the shortlist. Neither Brighton Pavilion nor Islington North is now in Labour hands, though it is unlikely that a change in candidate would have altered either outcome.3

SNP politics wrong footed me in 2023, and did so again this year. I predicted (with low confidence) that Humza Yousaf would survive through to the general election, and when asked who might succeed him I predicted someone who could run as socially progressive and a fresh start would defeat Kate Forbes, who I saw as too socially conservative for the members. The last bit proved right, the rest did not. Yousaf stumbled on a few months, before a decision to unilaterally withdraw from the SNP’s coalition with the Scottish Greens blew up in his face (another outcome I would never have anticipated). Yousaf resigned when he realised the lost Green votes meant he could no longer win a confidence vote. After Kate Forbes decided against running, John Swinney was elected the new leader unopposed. Swinney, a 60 year old lifetime SNP veteran who served a previous term as leader 20 years ago, has provided steady leadership after a chaotic year, but he is no one’s idea of a “fresh start”.

Some odds and ends: I predicted Labour would win the Wellingborough by-election, not a hard forecast despite the large Tory majority given the opposition’s track record by that point. They duly did, on one of the largest Tory to Labour swings ever recorded. I was asked if legal charges would be brought regarding the COVID procurement scandals. I said that looked highly likely (90%) given how such stories have progressed. I haven’t been following them closely since, but it seems someone from Michelle Mone’s PPE company Medpro was arrested in June, though Mone herself remains in the House of Lords and hasn’t to my knowledge been charged.

I was also asked whether there would be any meaningful move on House of Lords reform in 2024. I said I was 95% certain there would not, because there wouldn’t be time after a late autumn general election for Labour to move on this - but that I was 80% certain there *would* be meaningful movement in 2025 given Labour’s stated desire to make changes. This proved wrong on the timing, but right on the substance: a summer election gave Labour more time, and a bill to remove the remaining hereditary peers is already making its way through Parliament. I was right that Labour was serious about making some changes to the upper house - though its not clear whether the current bill will be the first of a package of reforms or their last word for now.

Finally, there were some prediction about the timing and administration of the election itself. I predicted, with relatively high certainty, an autumn election (50% October/November, 25% December). While I though May was possible (20%) I gave no chance at all to a summer date, which didn’t seem to make any political sense, so I thought Sunak would avoid it. Shows what I know.

I did, however, correctly predict that there would be no removal of donation limits - the Tories had already raised these in late 2023, and there was no sense in making further changes which looked more likely to benefit a flush Labour party than a struggling government. So it proved - indeed the Conservatives’ choice to raise the spending limit in November 2023 backfired on them in the election campaign, as their Labour opponents outraised and outspent them.

I was also asked about the impact of voter ID. While I correctly predicted this would have no substantial effect on the result4, early analysis by researchers on the British Election Study team suggests it did have a detectable impact on the partisan balance of voters able to vote, discouraging supporters of Labour and other smaller parties who were less likely to have the required forms of ID, and benefitting the Conservatives, who were more likely to have them. A small thumb on the scale but a thumb on the scale nonetheless. Given the weak evidence base for obstructing access to the ballot by demanding ID, and the haphazard selection of identity documents accepted at present, I think there is a high chance of Labour reviewing and reforming these rules, perhaps before voters go to the polls again in May 2025 local elections.

Predicting Dutch, German and American politics

Finally, a haphazard miscellany of global politics predictions I was asked for my predictions on only three non-UK countries’ politics, which ended up reducing my capacity to embarrass myself with hopeless predictions about contests I know little about in the bumper “global year of elections” just past. Still, I managed plenty of flubs even with a brief of three fairly familiar nations.

I was asked when the Dutch would get a new government and who would head it. I got both answers wrong. I figured the Dutch, like their neighbours the Belgians, would be content to run a caretaker government all year, keeping their outgoing veteran PM Mark Rutte in charge while wrangling over who should replace him. And I predicted that the PM who would, eventually, emerge would be controversial radical right leader Geert Wilders. Instead, the Dutch took their lessons from Italy rather than Belgium, putting an independent civil servant at the help of a four party coalition following a comparatively speedy six month process (Rutte’s final coalition took 299 days to negotiate) - the government was sworn in on 2nd July.

Wilders proved more flexible, and more aware of his own unacceptability to others, than I had anticipated, taking no cabinet position at all in the new government. Instead, Marie-Fleur Agema, a younger, female member of his PVV party became one of four deputy Prime Ministers - perhaps example of the broader tendency of European radical right parties to put forward female politicians in leading positions in an effort to “detoxify” themselves with voters. This gamble has paid off for Wilders so far - his party has had large leads in the polls ever since the last election, though it has fallen back a bit since the government was formed.

I was also asked about German regional politics - hardly my speciality - and in particular whether the radical right AfD’s surging support would prevent the formation of stable state governments in Saxony, Thuringia, and Brandenburg. Here’s what I said: “given the current state/trends in polls seems likely (70% chance) that at least one of these states will have no stable non-AfD govt option - either because AfD are close to a majority or because oppo parties can't agree a coalition. Which would mean an AfD state premier somewhere, with potentially major consequences for German federal politics.”

As 2024 draws to a close, this looks likely to be wrong on the most important point - the AfD aren’t going into state government anywhere yet. The AfD did surge in all three states, but in both Thuringia and Brandenburg state governments have now been formed which both exclude the AfD. Saxony has proposed a minority CDU-SPD coalition which also excludes the AfD but it is not clear if this government can secure the confidence of the legislature (the outcome likely depends on the AfD itself). So despite some very messy election results, the cordon sanitaire against the AfD held up in all of these states.

Last, but not least, America. I wasn’t actually asked for a straight prediction of the Presidential or Congressional elections but, based on what I said in other contexts in the time, I am sure I would have got two out of three wrong, predicting a narrow win for Biden over Trump in the Presidential election (due to an inaccurately low assessment of Trump’s ceiling) and the Democrats to retake the House of Representatives (expecting Dems to do better in the race for the House - which they did, but not by enough), while correctly expecting the Republicans would re-take the Senate (the Senate map was very hostile for Dems).

The mention of Trump and Biden also illustrates what else I got right and wrong. I correctly predicted that the Supreme Court would throw out efforts to keep Trump off the ballot, and that his multiple legal difficulties would not prove to be much of a barrier either. I said he wouldn’t go to prison, and that he would run. Indeed, running and winning was the best way for Trump to ensure he wouldn’t go to prison. So it proved.

No country for young men

I got Biden wrong. I expected him to run again, which he did, get nominated again, which he did, and then carry on, which of course he did not. I was, like many, taken in by what in retrospect looks like a rather aggressive PR operation by Team Biden to camouflage their candidates frailty and decline. But that is on me too - I did not take the increasingly obvious warning signs seriously, and I overestimated the institutional barriers to removing Biden once he became too much of a liability. I was, therefore, surprised by his disastrous performance at the first debate, and surprised by the (relatively) smooth process to replace him.

I should not have been surprised. The risk of an octogenarian doing the world’s most demanding political job going into a steep and career ending decline was always significant. The lack of a historical precedent for replacing a renominated candidate just reflects the lack of past precedent - there had never been an incoming President as old as Biden, so the chances it could produce new dilemmas and force new responses was not something that could be read from the historical. This is something to bear in mind when President Trump starts his second term aged 78 - the same age Biden was when he began four years ago. Trump’s age adds yet another source of uncertainty to a Presidency which will not be short of surprises. Expect the unexpected will be a good rule of thumb for politics on both sides of the Atlantic in 2025 and beyond.

Emily Thornberry is the main exception to this - having served on the front benches for nine years under Corbyn and Starmer, she received no ministerial appointment in Starmer’s government and returned to the backbenches.

Labour did not prove entirely averse to celebrity candidates, running Gomez frontman Tom Gray in Brighton Pavilion, and former Blur drummer Dave Rowntree in Mid Sussex. They both lost.

I incorrectly predicted scenes of chaos at polling stations. In fact, with very low turnout across the board, there were no scenes of disruption that I can recall.

Hey, sorry if this is the wrong place to post them but I do not use Twitter so I'm going to try my luck here. I'm a big fan of your predictions so I'd like to give you some questions (I hope I'm allowed more than one, don't worry it won't be a lot).

1) Do you think some local opposition to Starmer's mayoral/"devolution" plans will impact the results of the local election? We've already seen vocal opposition from councillors in places like Cornwall so I myself am interested if it will have an effect. Could we see the rise of localist candidates?

2) Will anything be done to further Labour's manifesto proposals about HoL reform?

3) Will Badenoch last the year (assuming the Tories suffer at the LEs from Reform)?

4) Predictions re: state of UK-US relations, Starmer-Trump personal relationship, Farage factor and will there be a diplomatic crisis-causing scandal from either side. Also if it will have an effect on UK-EU reset?

5) Predictions re: Germany, Australia and Canada elections.

Higher education minister is not a top position but Warwick & Leamington MP Matt Western had been in the shadow role for some time, but instead a retread was brought in. Not clear why as Western is mainstream, but he doesn't even have a bag carrier's job. Prediction: Reform to win two by-elections in 2025.